Art is conditional.

As much as I’d like to believe that art is unconditional, and that the best art (given an open and fair consideration) can ascend beyond time and context into the universal, its tether remains firmly subjective, grounded in individual taste, aesthetics, and consciousness. If people were unchanged by internal or external factors, throughout their inevitable growth and entropy, I could hold out hope for this idea of a “timeless classic” at least at the personal level. But the older I get, the more I realize how much I’ve changed, and continue to change—along with my trailing tastes and concerns about art.

Here’s what I really mean: when I was 16, I whole-heartedly loved the art-house movie Wild at Heart, directed by one of my favorite directors at the time, David Lynch, and starring Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern. I owned a copy of the film on VHS and watched it many times through my college years and into my 20s. I could quote memorable lines, and remember thinking the roles played by Laura Dern and (less prominently) Crispin Glover were some of their best ever.

Watching Wild at Heart again at 49, I have to admit, I didn’t love it. And I’m a little sad to confess this: I barely liked it. But maybe some of the reasons I once liked the movie have eroded with time and maturity, and/or maybe they were watered down by the over-familiarity I have with the film. For example, I remembered the funny and intriguing parts very well, and perhaps was inoculated against their charms. Or maybe the reasons I didn’t like the film (at this time of life) was because of a much deeper understanding of Lynch’s sharp edges, his disturbing artistic vision, and the neurotic messages he likes to tell about human nature.

People change I guess. And since it took Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage’s character) more than seven years in movie jail (and 120+ minutes of screen time) to understand this truth about human nature, I will try not to feel too bad about the change in me that’s happened over the last few decades since last I watched Wild at Heart.

What Wild at Heart is about

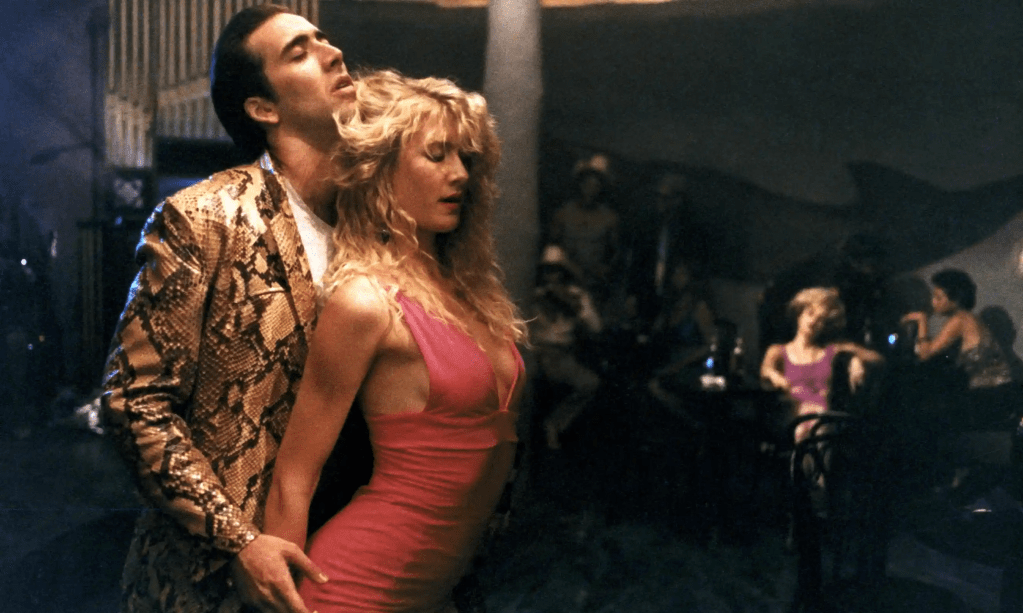

This erratic, erotic, and often violent love story is the tale of convicted killer, Sailor Ripley (Cage) and his barely-legal girlfriend, Lula Fortune (Dern) as they traverse the forgotten highways, the downtrodden back alleys, and the seedy underbelly of America’s southern meridian. As with any Lynch production, there is an assorted cast of freak-show criminals, bizarro fetishists, able-minded invalids, and run-of-the-mill margin-istas that show up in the most common and desolate backdrops of towns like New Orleans and Big Tuna, Texas. The main arc of the story is about Sailor breaking his parole to sweep Lula across the country and away from her certifiable “wicked-witch” mother, Marrietta (played by Diane Ladd), who enlists a pretty rough crowd of malcontents (e.g. Crazy Eyes Santos and Mr. Reindeer) as her search-and-destroy agents to rescue her daughter, and, hopefully, kill Sailor (who witnessed the murder of Lula’s father by Santos, and spurned Marietta’s advances). There’s always much, much more at play in a David Lynch storyline than a few summary sentences like this can do justice to, but this is basically the plot of the movie and what you need to know about it.

What I remembered about Wild at Heart

I remembered that Wild at Heart was based on a book (not this one, but this one) which I read. I must have read the book AFTER watching the film, but oddly Lynch’s movie actually premiered at the Cannes Film festival PRIOR TO the book’s first publication. I found out recently that Lynch wrote the screenplay and vetted it with author, Barry Gifford, and that the author continued to write Sailor / Lula stories post-WAH that are now packaged into a compendium. I don’t recall many details of the novel, but am sure that Lynch’s screenplay and directorial flare added to the already oddball nature of the book (for example: The Wizard of Oz callbacks, the cameos by Twin Peaks actors, the Angelo Badalementi soundtracks, and the Elvis-channeling of Cage.)

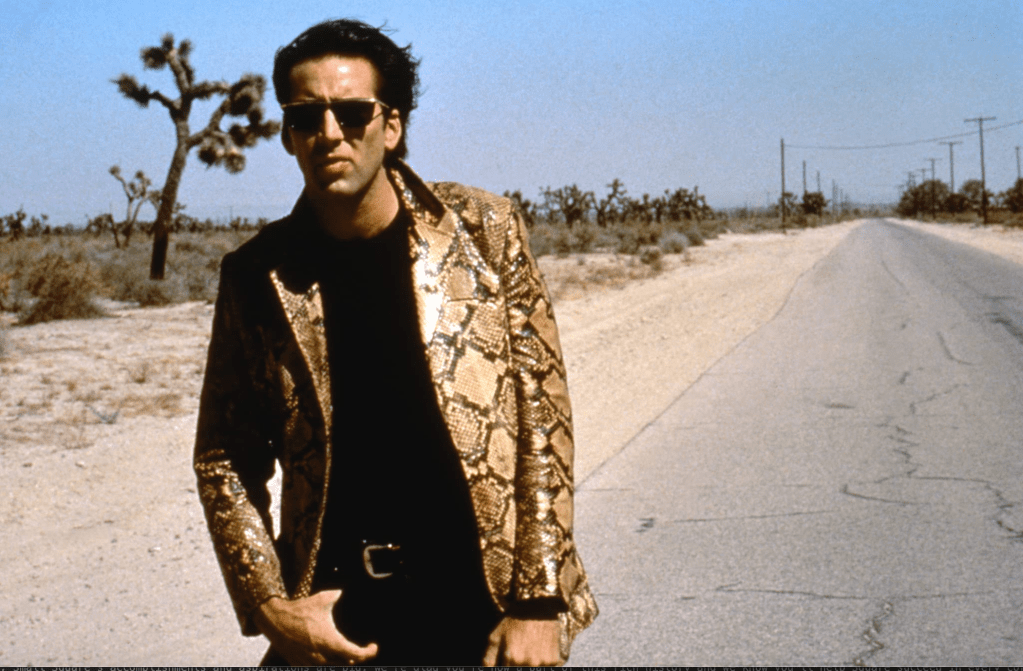

I also remembered that Sailor and Lula were eccentric, redneck, horny, and dim-witted sort of characters. Sailor opens the movie by violently killing a man who was threatening him with a knife, and winds up going to jail for manslaughter. After serving his time, we see Sailor post-release being picked up at the prison by Lula (his “Peanut!”) who brings him his snakeskin jacket, “Hey hey hey my snakeskin jacket! Thanks, Baby! Did I ever tell you this here jacket represents a symbol of my individuality and my belief in personal freedom.” This Bonnie-and-Clyde couple’s undying and obsessive devotion to each other (with accompanying post-coital philosophy) is what holds the film together.

I also remembered Crispin Glover’s neurotic minor character Jingle Dale, who was obsessed with Christmas, stayed up all night making sandwiches (“I’M MAKING MY LUNCH!”), wore underwear covered in cockroaches, and crept across concrete like a tightrope walker to prevent himself from stepping on a crack.

I remember quite a few of the great quotes from the movies.

Like this one from Lula that sums up the entire film, “This whole world’s wild at heart and weird on top.” Or this one from Lula to Sailor, that sums up the human anguish and suffering the two, even in their love, cannot entirely avoid, “I wish you’d sing me Love Me Tender. I wish I was somewhere over the rainbow. It’s just shit shit shit.”

Or this strange (Lynch-esque) soliloquy from another Twin Peaks alumn Jack Nance playing the character 00 Spool, “My dog barks some. Mentally, you picture my dog, but I have not told you the type of dog which I have. Perhaps you might even picture Toto, from The Wizard of Oz. But I can tell you my dog is always with me…[Barks loudly]”

What I’d forgotten about Wild at Heart

The main thing I forgot about Wild at Heart is that it appealed to me most in my time of early adolescence, a time defined by strong sexual urges, anti-establishment leanings, testosterone-fueled rage, and youthful ennui and rebellion. Like so many 16 years old before and after me, I was in that age of resistance (the raging against the machine) where everything about my WASP upbringing begged to be dismantled, destroyed and mocked. In the same way that young men in south America reacted so strongly to Rumble Fish, I must have gravitated towards the avant garde nihilism of David Lynch, the anti-hero of Sailor Ripley, the unbridled allure of Lula Fortune, because those artistic expressions and characters spoke to something deep within my troubled and lustful psyche at the time. I don’t think any of that resonance was bad per se, but it’s just a lot harder to take Lynch seriously now. I see this film as tragically absurd (Don Quixote chasing windmills) rather than subversively heroic like I’m sure I did back then.

I also forgot that the power of Wild at Heart at the time of its release was that it granted access to a portal into an underworld that I did not have access to, prior to the invention of the internet. I was sure such a distorted world must exist (even if exaggerated) and it was a similar darkness I felt in myself, too; I wanted to explore it. Wild at Heart was also alluring to 16-24 year old me because it stood in stark contrast to the puritanical evangelical Christian world I grew up in. It was off-limits and morally reprehensible, so therefore exquisitely enticing to me. Before there was the internet, there was Wild at Heart, a place where within 120 minutes you could get: pornography, fetishes, gore, graphic violence, drug use, lawlessness, hardcore music, karate dancing, snuff film scenes, car wrecks, fistfights, Elvis impersonations, old people and nude fat people dancing, and all kind of bawdy humor and swearing. I, mean, c’mon, what red-blooded American male isn’t going to sign up for that kind of peepshow? Especially when so much has been repressed and denied.

But I gotta say it was weird watching that stuff now.

For me, it no longer titillated or shocked. If anything, it kind of bored me at times. It dragged on too long, or seemed to lack a cohesive purpose. For example, seeing so many scenes where random maids or escorts were standing around topless, as boring sex props for the “hard men” they were designed to serve in the scene, just made me grateful that Twin Peaks had to adhere to the more stringent censorship rules of prime time television. Twin Peaks (at least the first season) was a far superior product perhaps because of some of the constraints put upon Lynch’s vision for the good of a more mainstream audience.

Added to this are the more disturbing storylines like Lula’s, who has repeated flashbacks of being raped by her “Uncle Pooch,” is shown on the operating table under a comically distorted magnifying glass while getting an abortion, and is sexually assaulted by the ultra-creepy Bobby Peru, played by Willem Dafoe. When experiencing these things as an empathetic viewer (with little to redeem or make sense of the narrative purpose) you end up feeling much like Lula did in the film, like you’ve been forced to sit in a shitty hotel room for days and days while smelling the stale vomit that you spewed on the carpet, but were too weak to clean up. I may have been able to tune those realities out back then, as being too far removed from any real world context, but as an adult I know more. I know all too well that women are raped, they are sexually abused, they do get abortions, and are put in untenable situations with villainous men–and that shock value is not enough to justify the use of such content without a more elevated or cautionary message.

What made the rewatch worthwhile for me

This post is getting long so let me just do a few quick hits here. While watching this movie was not what I expected because of the passage of time and my own evolution, I will say these things made me glad I did:

- Hearing Chris Izaak’s Wicked Game. Yeah, I’ll admit it, it’s cheesy, but I like it.

- Seeing Sherilyn Fenn in a non-Twin Peaks role. She’s pretty underrated and should have been cast more.

- Seeing Sheryl Lee (Laura Palmer!) as the Good Witch who lead Sailor back to Lula in the end.

- Seeing Bobby Peru get his head blown off (justice served) and then a dog runs off with a severed hand.

- All the great dancing scenes.

- The last scene where Sailor picks a fight with a bunch of punks when he knows they are going to try to beat him up anyway, “What do you fags want?”

- Sailors swollen-nose singing of Love Me Tender (which professes his desire to live happily ever after with Lula) that roles into the credits.

- The old farmer guy in the overalls snapping and eyeing Lula at a gas station.

First for Nicolas Cage character in a film as Sailor Ripley

- Beating the brains out of someone (literally)

- Accosted by a woman in a restroom (karma baby, see Vampire’s Kiss and Valley Girl)

- Dancing to death metal in a club (new genre)

- Buying a girl a candy necklace

- Balancing a radio on his outstretched feet

- Wearing a snakeskin jacket

Repeat occurrences

- Pantyhose on head botched robbery (see Raising Arizona)

- Points finger in an Elvis pose (see Vampire’s Kiss)

- Third appearance with Crispin Glover (see Best of Times, Racing with the Moon)

Best Nicolas Cage lines from the film (other than the “jacket as symbol of individuality and personal freedom” line)

““The way your head works is God’s own private mystery.” To Lula.

“I guess I started smoking when I was about…four.”

“Rockin’ good news!”

“They say the eagle flies on Friday.”

Art is conditional. And while I may never look at Wild at Heart in the same way that I once did, there was a condition (a time, a place, a situation) in which the movie appealed to some deep-seeded need in me to relate to the outsider, the outlaw, and the forgotten, of which I believe Nicolas Cage may be the patron saint.

Rockin’ good news!

Leave a comment