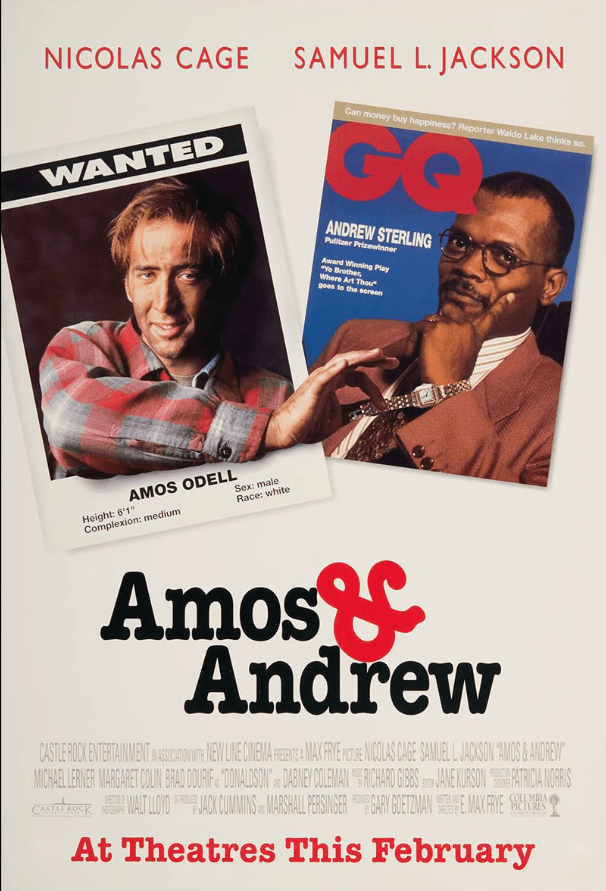

When Samuel L. Jackson’s agent sent him the script to 1993’s Amos & Andrew his first reaction was “nope” based on the racially ignominious title alone (e.g. see Amos ‘n’ Andy). His agent said, “read the script” and Jackson did and was intrigued by the role, “Where are we going with this?” he wondered.

Jackson’s concern was the exact same one I shared when I first started viewing Amos & Andrew as the next stop on the WATC(H) journey. After all, a lot has changed politically/socially since 1993 and this white-guy (E. Max Frye) production was not exactly a Spike Lee joint.

I was right to be concerned and if I had to review the movie in one word, the word I’d choose is: UNEASY.

I’m not sure how Jackson feels about the movie in hindsight (I’m sure others have chased this information down, but feeling lazy today so will leave it to my imagination) BUT let’s outline the plot and you can tell me if it makes you uneasy or not.

Amos & Andrew Plot

Andrew Stirling (Jackson) is a Pulitzer-prize winning author who has purchased a vacation home on a well-to-do island somewhere in the northeastern U.S. (Massachusetts). While moving about his new home at night, some nosey white neighbors, Phil & Judy Gilman, spy Andrew through a window using some stereo equipment. Unaware that Stirling has purchased the home from their previous neighbors, the ignorant Gilmans assume Andrew is a thief and call local law enforcement.

Chief of Police Cecil Tollivar (played by Dabney Coleman) and his deputy, Officer Donnie Donaldson (Brad Dourif) show up in force to apprehend the “intruder.” The situation escalates very quickly as the group of yuppie yokels spin up a paranoid (racist) fiction-reality that this “obvious” break-in is also a hostage situation (even though there’s no actual evidence of any of this.) Some local journalists also get involved as well reporting the story as it is unfolding.

Stirling who is unaware that his house has been surrounded by witch-hunting whiteys, hears his car alarm go off and ventures outside to disarm it. Mistaking his key fob for a weapon, Deputy Donnie opens fire and the other jumpy policemen follow suit. Andrew, unaware of who might be shooting at him in the dark, dives back into his home (terrified but unharmed) believing himself to be under some kind of home invasion. Chief Tollivar calms the situation and “gets a line” into the home where he speaks to Stirling (whom he believes to be one of the hostages.)

Piecing the conversation with Andrew together, Chief Tollivar realizes the mistake his force has made and that they have nearly killed the actual home-owner, a Pulitzer prize winning author. Since it’s an election year, and Tollivar has political ambitions, he hatches a plot to try to fool Andrew into thinking there is an actual intruder in his home (e.g. he is the hostage) and he has a ready patsy for the hostage-taker sitting in the county jail, in the small time criminal Amos Odell (played by Nicolas Cage).

Pressuring Amos to take part in the ruse or face more serious consequence with a connected judge, Tollivar persuades Amos to enter Andrew’s home pretend to be his captor and then give himself up to the police. In exchange for this, he promises Amos he can flee the country to Canada and the police will not intervene.

With limited options, Amos agrees to this arrangement even though he is unaware of who Andrew is and why this farce needs to be played out in the public eye.

The rest of the movie takes us down the forced path of contrived conjecture: what happens when a poor white criminal and a successful upper class black man are cooped up in the same house together and have conversations about life.

What could possibly go wrong?

Take it easy, uneasy.

The unspoken message I get about race relations from Amos and Andrew (especially from Odell’s character) is just to “take it easy” and not be so uptight about racism. The messaging is tired but predictable: We have more in common than we think, we can learn from our different experiences, and by dismantling our unconscious and conscious bias we can find that common ground of true understanding and a shared humanity. This was all just a big misunderstanding–all 200+ years of our besmirched history. The problem with this is not the principles themselves, but that the scales once again (even in the lesson learning) are weighted so heavily in favor of the white man and diminish or entirely disregard the experience of the black man in this story (and by proxy in this country.)

The true irony is that even though the movie sets out to enact some uncovering of systemic wrong-doing in our thinking and meanwhile make some small artistic reparations for the injustices inflicted, so much of the dialogue, plot details, and character development FLIES IN THE VERY FACE of the very ideals it attempts to espouse. It’s like they said, “Let’s make a movie to dispel racist behavior (in a light-hearted way)” but somehow they still did it in a blatantly racist kind of way.

It makes me uneasy. And I think in 2023 (thirty years since the films release) it probably should. Here’s why.

The joke’s not funny anymore.

The premise of this film is that it’s a comedy. I don’t think it’s funny though. The premise is that this is a case of mistaken identity (fueled by long-held if veiled racist prejudice) because someone like Andrew, has moved into a neighborhood where he “doesn’t belong” based on the color of his skin and the norms of the town. The thing that the movie gets right is in depicting our base human nature. The Gilman’s, whom today we have pejorative terms for are Chads and Karens, cannot conceptualize the possibility that Andrew would have a valid and non-threatening-to-them reason for living near them in their glass castle existence.

Phil Gilman expresses it best when he says, “Believe me, Chief, I’m not racist, but when you see a black man on this island with his arms full of stereo equipment, you know damn well what he’s doing.”

Later Odell, whom we’re supposed to believe is perhaps a little more enlightened in his thinking because of being lower-class and not subject to elitist upper class bias, is shocked to discover Andrew is the “hostage” he is supposed to be taking. He even asks Andrew, “Sure you ain’t the cook, here?”

And Chief Tollivar who pretends to be the “white Savior” in this narrative, even though his only aim is to save his tenuous political career, blurts his true feelings about Andrew when he tells Odell, “We don’t want the N—– on this island, anyway.”

These cringe-worthy lines and characters are meant to be laughable, absurd, and cautionary, funny even; but the problem is that in the last thirty years, with the rise of the internet, the smart phone, social-media and a heightened collective awareness (from whites MOSTLY, as people of color have known the evil of racism all too well from personal experiences throughout America’s history) we know that the outcomes of these prejudice and discrimination can be and have been deadly and generationally life destroying (leading to genocide).

Racial profiling, police brutality, the war on drugs, mass incarceration, militant white nationalism, Black Lives Matter protests, anti-woke politics, and race wars fill our newsfeeds and weigh on the conscience of any self-reflective American today. Not only do the modern day Chads/Karens/police, mistake the Andrews for Amoses, but they shoot down black youth who are jogging, they call the cops on them when they are walking in the park, and they shoot them while they are sleeping in their homes. These “innocent mix-up” events are neither innocent nor are they a confused / inappropriate action based on limited information. Instead they are racially charged systemic evil inner-life realities enacted in the outer world–and they are killing and destroying people of color. The analogy that comes to mind for me is that we are pretending the world is being policed by Barney Fife on the white-washed Andy Griffith Show when we all know it’s much more akin to The Wire.

How Andrew loses and Amos wins

Amos is the mediator in this movie, both as a character and as a storytelling device. While a flawed character, he’s just a “small-time” criminal and really caught up in Tollivar’s plot in the same way that Andrew is. We are supposed to trust him. He’s the white man who gets to enter the world of the black man and ask some questions (all white people want the answers to, but are afraid to ask). This ALSO made me uneasy because it felt so self-serving, contrived, and tone deaf to the issues it seeks to address.

Amos is everyman wanting to know what it feels like to walk in another man’s shoes, and as stated in the Samuel Jackson interview with Bobbie Wygant, he expresses how we all want to “move up and out and around.” But from the very beginning of the relationship the balance of power shifts firmly to Amos and it really doesn’t ever shift back, nor does it seem to question this white-over-black power dynamic. One man is defending himself with a frying pan, and the other has a sawed-off shotgun and a society at his back.

Here’s another example. When taking Andrew hostage, Amos duct tapes him into a chair:

[AMOS] “Don’t worry, bro, this is just for appearances.”

[ANDREW] “I’m not your brother.”

[AMOS] “Nothin’ personal.”

This interaction is perhaps more telling than I think the director intended for it to be. Just like America’s long tragic history of slavery, the black man is again shown here as merely a piece of property or a prop for appearances (status, entertainment, etc) meant to expedite a transaction. For Amos, Andrew gets him a list of demands, “I WANT A MILLION DOLLARS, AND A HELICOPTER OR I BLOW HIM AWAY! THANK YOU!” Amos screams at the police chief.

In an interview, Samuel L Jackson said given his choice, he would have played Andrew in a more “Afrocentric manner.” He said he liked the opportunity to play a different type of character and grow as an actor (i.e. playing an educated, successful, upper class black man) but I wonder (based on many of the roles he’s had since) if he would have taken a role like this later in his career. Or would he have used his acquired power as an actor to cast Andrew as an angrier character? Would he have fought back against his captivity a little more?

Here’s some the ways that I think Andrew loses and Amos wins in the film.

- Andrew doesn’t try to escape. He seems passive. Everything just happens to him and even when given the opportunity to ditch Amos, he doesn’t. (He even teaches Amos how to tie a tie.) This lack of self preservation and fatalism in the face of his situation creates a victim blaming (Stockholm syndrome?) situation with the viewer where you remain unsympathetic to his condition and/or blame him for not standing up for himself. It’s weird.

- When Andrew questions Amos about what he knows about “living with dark skin”, Amos take the opportunity to lecture Andrew on how he is supposed to identify, “I know for all your damn talk, you’re about the whitest black man I’ve ever met.”

- The only counter to this, is the discussion Amos has where he talks about how his father worked in the white man’s world and was very successful in it, but then died shortly after retirement and was not remembered / mourned by any of his white co-workers. “My father made it in the white man’s world. He wanted his son to make it in the white man’s world, too. But don’t for one second think I’ve forgetten where I come from.” The unspoken message here is that he accepts the concept of “arriving” being some acceptance of the white man’s world as the ultimate / prescribed attainment as long as one is rooted in the tradition of his past.

- Andrew’s house gets burned down, not by the racist white establishment that has profiled and tormented him, but by the black activists who have come to help his cause. He seems completely unphazed by this at the end of the movie though he’s done nothing wrong other than choosing to move in close proximity to such deplorable people.

- Amos has a captive audience for all of his own therapy / confessions (with a bizarrely funny story about Sea Monkies).

- Andrew solves the car key fob problem which allows the two to escape. Amos gets away from the law and the consequences. Andrew gets back to his wife, but again has a burnt down house for his reward.

I think you probably get the idea of why this movie made me uneasy and it was likely not for the same reasons that the director wanted to make the white man uneasy. In the Jackson-Wygant interview, she asks Jackson if he thinks the white audience and black audience are “laughing at different things” in this film, and he replies that he thinks this is definitely true. I’d argue that for the modern audience, they can no longer afford to laugh at the same things or at the differences portrayed in this film. The reality-reflected art portrayed here is no longer fictitious or hypothetical, and the stakes (as we know) are so much higher and more dire for us a society.

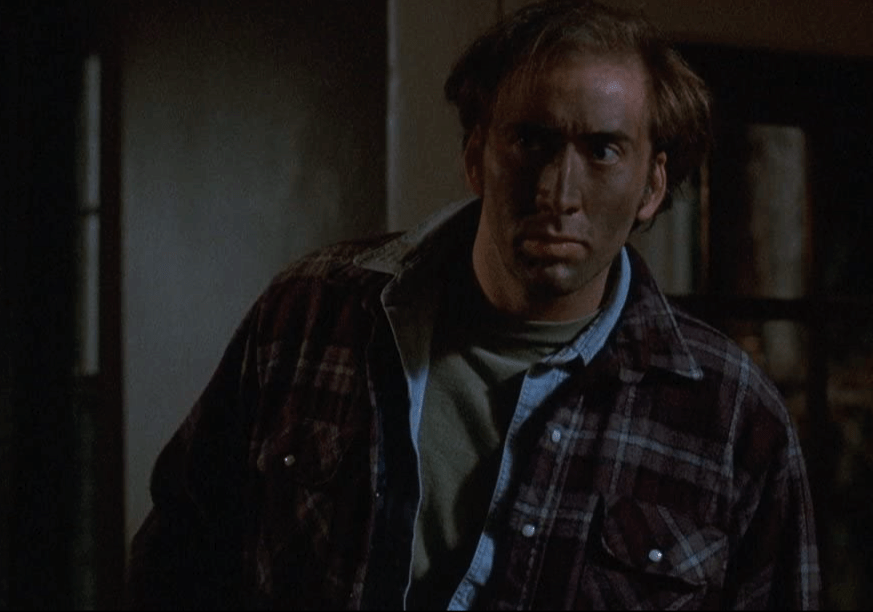

BUT, this was still a Nicolas Cage movie, so I need to share a few things I observed about his performance:

- Cage a creeper? Hate to point it out, but he takes on another “creeper” role here where he gets in trouble for dating a minor, “She looked 18…” and the scene where he is flirting with the much younger than him pizza delivery girl? Eek. Pedophile much. Geez.

- Geographically challenged. Amos thinks he’s in Canada when he tries to “exchange” small bills at a bank and he gets arrested. “I thought it was Canada…yeah, well, I flunked geography and my sense of direction sucks.” (He heads south at the end of the movie thinking he is headed to Canada again.)

- Spastic man! He’s hyper-expressive, always doing things with his body. As he’s sipping his first beer outside of jail, he swings his head in two full arcs.

- Gymnist Cage. Does a few handstands while killing time in the jail cell.

A few non-Cage factoids

- Andrew’s Pulitzer prize winning book was Yo Brother Where Art Thou?

- Sir Mix-a-lot raps a song at the end as the credit roll called Suburbian Nightmare

- The movie employs a throwback reference to black-face a few times (Donnie for “night ops” and Odell because…who the hell knows? Why? I kept asking. Just why?)

- The Chad/Karen couple face no consequences for causing this whole debacle even though they are arguably the most despicable characters in the show (other than Tollivar). They are also drug users (think War on Drugs) and enjoy secret S&M sexual games as well.

- There are also bloodhounds used to hunt the escaped “convicts” in this movie (nodding back to escaped slaves in the South, perhaps?). Amos hates dogs.

- Chief Tollivar getting tied up in a chair reminded me of 9 to 5 where he played a sexist pig instead of a racist pig. I’m sensing a trend here…

Firsts for a Nicolas Cage character as Amos Odell

- First time with a toothpick and a gold tooth

- First time ordering a pizza and eating Doritos

- Hostage situation

- Doing donuts in an empty field

- Toting a sawed-off shotgun

- Smoking weed

- Learning how to tie a tie

- Suffering from hay fever symptoms

- Wrestling with a black man on the front lawn

Recurrences

- Criminal activity (Multiple)

- Unique tattoos, i.e. a 4-Ball (see Raising Arizona, Moonstruck, Fire Birds, and almost Racing With the Moon)

Conclusion

Gotta say I’m glad to have this one done and in the books. It was an uncomfortable watch and an uncomfortable review for me. Sometimes the best artistic intentions can still lead to a very misguided and unintended result. Would love to see this movie if we could just remix it now for a modern audience and have Spike Lee or Jordan Peele direct and write the script.

Leave a comment