Saving someone’s life is like falling in love. The best drug in the world.”

“I’d always had nightmares, but now the ghosts didn’t wait for me to sleep. I drank every day. Help others and you help yourself, that was my motto, but I hadn’t saved anyone in months. It seemed all my patients were dying. I’d waited, sure the sickness would break, tomorrow night, the next call, the feeling would drop away. More than anything else I wanted to sleep like that, close my eyes and drift away…”

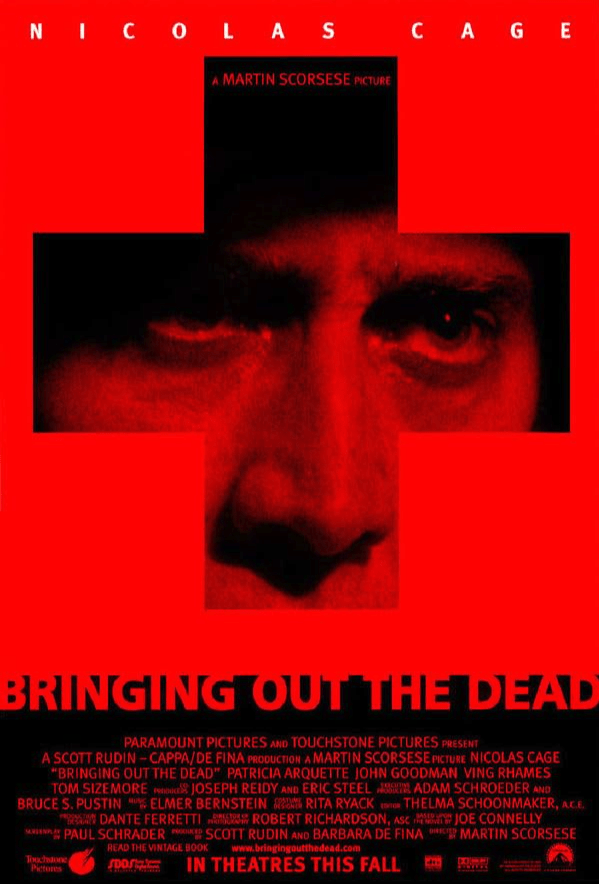

These two quotes were spoken by Frank Pierce, the Hell’s Kitchen paramedic (played by Nicolas Cage) in the Martin Scorsese directed film Bringing Out the Dead (1999). In the movie, based on Joe Connelly’s semi-autobiographical novel, Frank is going through a crisis of faith and vocation. The life he is chosen to live is killing him slowly, draining his soul of meaning and purpose, driving him to destructive behaviors. Making him suffer.

I can relate to Frank’s story 100%.

Not because I am a medical doctor or have ever been in the position to literally save someone’s life (ok, my niece as a toddler fell into a pool once and I hoisted her out) but because I once believed I could save a person’s soul quite literally from damnation. And I built a vocation based on that belief.

So yeah, I can attest to the addictive allure of having a messiah complex and I can also bear witness to the destructive wake of leaving that kind a “high” behind (letting go of that chosen sort of suffering). I can imagine exactly how Frank Pierce feels (well sorta).

The Scorsese movie you didn’t see

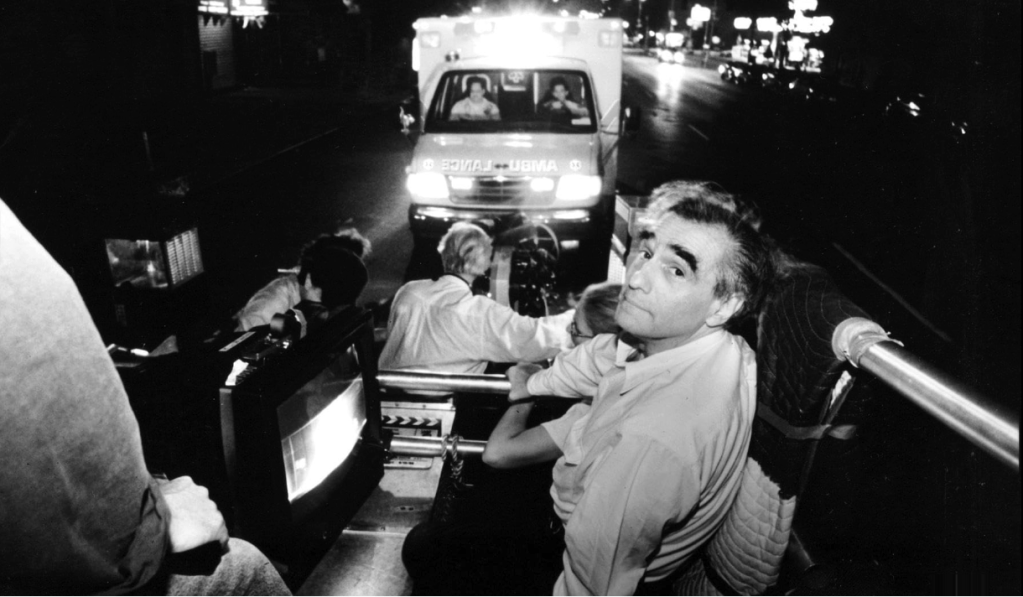

When you think of the director, Martin Scorsese, you probably think of one of a few things. You may think of his gangster movies (Mean Streets, Goodfellas, Casino, The Departed) or maybe you think of Robert DeNiro (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Cape Fear, The Irishman) or, if you’re like me you think about movies that are directly or indirectly tied to spirituality, faith, Catholicism (The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun, Silence), but what you probably don’t think of Nicolas Cage or the movie Bringing Out the Dead.

That’s because, like me, you likely missed it in 1999 when it came out in theaters OR you went to see it in theaters (mistakenly thinking it was a car chase movie) and were disappointed OR you don’t have a Laser Disc player (never did) and never realized this was one of the last movies printed in that format (which is an unlikely but weirdly true fact).

Either way, you missed seeing a gem. But that can now be corrected, thanks to the power of digital media.

Whatever the case, you should take two hours and watch this trauma-heavy movie with a title that jokingly came from the “not dead yet” sketch in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

You should watch it because Nicolas Cage is in it.

And you should watch it because sometimes our suffering is self-inflicted and requires some penance and self-forgiveness.

The movie is a mood (and it is mystery)

My typical formula for writing these WATC(H) reviews:

- Summarize and describe the movie (in way too much detail)

- Draw out the ‘ah-hahs’ and the ‘oh-yeahs’ and the quirky observations about Nicolas Cage.

- Touch on or unpack the cinematic craft,

- Highlight the good Cage quotes, and

- List the Cage-character occurrences (first / recurring) in light of the other movies he’s been in.

But having spent the better part of a Sunday trying to summarize the plot of Bringing Out the Dead to no avail, I’ve decided to scrap the typical formula and take it in a different way.

If you are interested here’s the list of failed (valiant) attempts::

- The first draft was too theological / lit-critical.

- The second draft was too hyper-descriptive of the minutia of each scene and character.

- The last draft was too procedural. (Gag. There was even an FAQ.)

What this tells me is that the subject matter is bigger than my thoughts can contain in a typical post; that my feelings are too intertwined to simply let a few details slide. That I am grappling with trying to articulate something bigger than a movie–that I am in the realm of ideas and philosophy.

I know, right?

In other words, this movie is a mood. In Christian religious lingo it’s “mystery”.

I don’t mean Agatha Christie or anything like that. What I mean is that this movie is mystery in the sense that it is not something we simply don’t know (was it Colonel Mustard, in the lavatory, with a monkey wrench?) but it is something that we can’t know by its very nature. That’s not to say we can’t reflect upon mystery, attempt to describe, grapple with, appreciate and feel it. But what I am saying is that it is futile to try to dissect mystery, or analyze it, or bottle it up and stick it into a clean review formula–and expect that to translate or satisfy.

Trying to do write a film review for mystery left me unsatisfied.

Am I overthinking it? Probably.

So let’s talk about our feelings instead. Let’s talk about mystery.

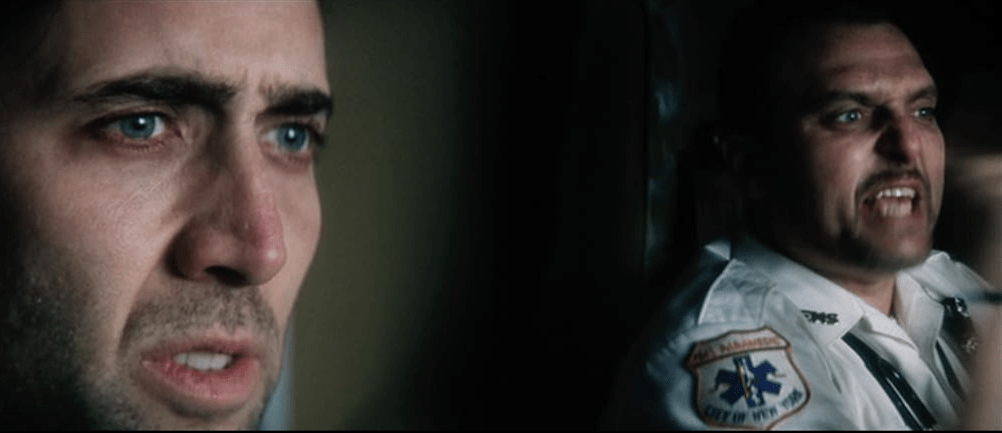

The mystery of being Frank

I feel empathy for Frank. Frank Pierce is a paramedic who is tasked with a very difficult job. He is a graveyard-shift paramedic working in Hell’s Kitchen in the 1990s. (Some have suggested that this version of 1990s New York seems a lot like the crime-ridden New York of the 1970s. It feels dire, dank, and hopeless in Scorsese’s vision. It was the New York that he knew way back when, but that’s neither here nor there, because it not about the external setting, but rather an internal one that Scorsese is concerned with…) Frank is awake, working, when most of us are asleep.

Frank’s job is impossibly difficult. When people overdose and start to choke on their own vomit, he gets the call. When young men are shot full of bullets and are bleeding all over the street, he is there with them. When a heart attack strikes or an apartment burns or a woman goes into labor, Frank is speeding to the rescue, alert and ready to act as a shield against oncoming death.

For Frank, there is not a slow start to the day, that eases into a few meetings, a lunch break, a few more meetings, a coffee break (maybe a stroll) and then end of the day.

Instead there is just a violent rolling barrage of unplanned trauma, sleep-deprived escalations, unprioritized emergencies, and uneasy armistices that may or may not allow him enough seconds to throw some coffee or a few bits of food into his mouth before the next tragedy lurches into his walkie-talkie.

There is no plot to this kind of day, and in some ways there is no plot structure to Bringing Out the Dead. I could tell you what happens sequentially, but it’s meaningless to do so. The movie is about 72 hours of mayhem and human suffering. On one level, the film is only about three straight nights working with Frank, looking over his shoulder as he deals with situations and people trapped in hell. For example, Frank:

- Resuscitates an old man, Mr. Burke, who has had a cardiac arrest (only to see him end up in a coma)

- Transports a habitual drunk to the ER (Mr. Oh) a man who looks and smells worse than a corpse,

- Convinces a suicidal man Noel to live (by promising to kill him in a clean, hospital setting)

- Fails to save (but comforts) a gunshot victim who has promised he’s going to change his ways (Omar from the Wire! RIP)

- Resurrects a heroin-ODed punk rocker named I.B. Bangin’ by shooting him full of Narcan.

- Delivers two twin babies, made by a “virgin” couple in a crack house, watching one child die while the other lives.

- Rescues an impaled drug dealer before the two can plummet to their deaths from a high-rise balcony

- Berates a half-hearted suicidal for being weak in throwing away what so many stronger dead people wanted: their life,

- Saves Noel, the psychotic whom he promised to kill from a truly psychotic beating by his co-worker

- Euthanizes the old man, Mr. Burke, that he saved in the beginning, because that’s the more compassionate move.

But knowing all of these events and trauma’s sheds no light on the why behind Frank.

Frank is mystery. Not a mystery. Mystery.

Why would Frank want to do these things at all? Is he an adrenaline junky? Is a masochist? What reward (monetary, ethical, or otherwise) could he possibly receive that would make up for all these human horrors he is subjected to?

And there lies mystery (and the beauty) in Bringing Out the Dead. Frank knows at some level (altruism, ego, conscience, adrenaline), but he can’t really know why he does these things. Is it to save lives? To be like God? I think that interpretation is way too simplistic.

Because even when he doesn’t want to continue to do this job, and he emphatically wants wants an out, he can’t stop himself.

For some, compassion is the strongest addiction.

The mystery of being me (to just get the Cage stuff scroll down)

Click here for the personal stuff

I am not Frank. Frankly speaking, (ahem) I am far from it. As a young man, I did have a bit of a messiah complex though. It was somewhat built into the faith tradition I grew up with, but that’s not really an excuse I am hiding behind.

To be an evangelical Christian meant that you were supposed to show compassion to “your neighbor” (everyone) by sharing God’s love with them, which really meant, in my experience of it, helping them see that your “Christian” way of viewing the world was the preferred way–and the way they (all humankind) should follow after and live up to as well. We’d call “our way” “God’s way” of viewing the world (and it was never forced or coerced on anyone) and yes there was a shared set of commonly held views that we ascribed to God, but coincidentally, it was also “our way” of viewing the world. That’s how dogma works. The thing you define for the world defines you.

For me, salvation meant saving someone’s soul and that was just as important (to me) as medical work (if you can get your head around that); shockingly we argued it was even more important because the soul is eternal and lives beyond the body. In the way that Frank sought to heal physical and mental trauma on the rough streets of New York, I sought to heal the spiritual wounds (and misguided behaviors / beliefs) of the world (and by world I mean, the people in the world not already adhering to my worldview). No pressure, right?

But like Frank, I even took this “calling” or vocational expectation more seriously by training to heal this soul sickness among the heathens of western China. I call them “heathens” (tongue-in-cheek because the word is so outdated even I am using it ironically) because they were well beyond the bounds of my Judeo-Christian worldview–because as Communists, Buddhists, and Muslims, to me they were just as removed from “true well-being” (i.e. the Christian faith) as were the pimps, prostitutes, and addicts from the healing powers of Frank and Our Lady of Perpetual Mercy hospital.

It sounds weird to read it back now, but that’s how I saw things. The self-importance, the power of the “calling”, the belief that everything you were doing could save a life (and would be counted as such in the eternal book-keeping) all of it compelled me to step deep into my own sense of suffering and martyrdom.

I moved to China. I began to bear witness. I felt it all. I tried to live like Frank. And I really, really crashed and burned emotionally.

The ghosts and the ghost

You get an idea above of what Frank went through (list above), but, thankfully, he didn’t go through it all alone. That would truly be hellacious. Frank had some flawed but faithful fellow pilgrims, guides, and tempters who journeyed the dark nights with him. Through the plight of the ambulancing we get three unique views / counterpoints into Frank’s character and his breakdown in Larry (John Goodman), Marcus (Ving Rhames) and Tom (Tom Sizemore). I like to think of them as either the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (keeping with the religious themes) or as Scrooge’s ghosts that visited him three nights in a row.

Frank is spiraling in this film before the action begins, but we get the first view into this through Larry.

Larry acts much like a somewhat distant father figure to Frank, providing paternal advice (you’ve gotta eat) warnings (you’ve gotta stop drinking so much) and moral values (you’ve gotta stop wasting time gawking at prostitutes). Larry has a plan for his retirement (reminiscent of the scripture, “in my father’s house are many mansions”) where he settles down as a Captain in a peaceful suburb where he can spend more time with his wife and children.

Larry, much like the Old Testament and wrathful moralist, Jahweh, can’t abide the drunkards and other wanton characters (like Mr. Oh) who destroy themselves with drink and distract the first responders from saving the ones “who really need it” i.e. deserve it.

Larry seems to have little idea how much Frank is already suffering, even though he was there when Frank first saw the Ghost. (Also, like the ghost of Christmas past, Larry can look backward to what’s already happened, but he can’t really help Frank in the present or the future.) Unless there’s beef lo mein on the menu.

Marcus, well, he’s the fun guy. Marcus is a sensualist and much like Jesus, the Son, (of the Bible) he likes a good party (water to wine), he likes the ladies (“always hangin with them hookers” groan the Pharisees) and he enjoys an over-the-top spectacle (miracles and wonders). On Frank’s second night, we are treated to Marcus and his stories (parables) about when to and not to use mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. He’s a jokester and a prankster. He’s in love with the female dispatcher “Ms. Love” and he’s pretty gregarious. Much like Jesus, Marcus is also compassionate, concerned about Frank’s mental state and his faith.

When Frank tells a folk story about a mighty wind saving a woman from jumping off a cliff, Marcus emphatically rebukes Frank’s empircal assessment saying, “that was Jesus!” When Frank and Marcus find a dead punk rocker at a club, Marcus asks the group to hold hands and pray for the boy–bringing him theatrically back from the dead (while not mentioning to the crowd the use of Narcan).

Marcus is also a bit of a charismatic con man or a snake oil salesman, but given the moral spectrum of this film’s characters, he is most definitely a saint. High on the adrenaline of just having saved a baby’s life, Marcus wrecks the ambulance, flipping it on its side. Frank, bleeding, and ecstatic jumps out of the vehicle, yelling, “I quit. I’m through.”

Marcus replies through the window, “Oh, you think just ’cause you quit, your ghosts gonna quit too? It don’t work that way, Frank. I been there, son.”

And then there’s Tom. Tom might be the Holy Spirit or he might be the Devil. Hard to say? Having tried and failed to be fired or quit his job multiple times, Frank cannot escape the Ghost. So he shows up to work on the third night completely frazzled. He gets paired with his old ambulance partner, Tom. Tom is always out for blood. You would say he’s an ambulance chaser if he wasn’t the one driving the ambulance.

Like the Holy Spirit who showed up like “tongues of fire” possessing the early Christians, Tom is the Holy Spirit who blows through a rabble crowd leaving what looks like chaos in his wake. No one knows how the Holy Spirit works or how it will move (according to Jesus), but it’s action-oriented one hunerd.

The problem with Tom is that he’s also a violent and volatile man; he’s a time bomb just waiting to go off, entirely enigmatic. With Tom, you never know if he’s actually out to save humanity or judge and damn them for their sins. In many ways, I see Tom as The Ghost of Christmas Future, except he’s not afraid to talk (and yell even), he’s in your face. And he’s in Frank’s face, showing him again and again what he’s trying not to look at head-on: death.

But much like TGoCF (and the Holy Spirit) he’s also the catalyst that changes Frank and causes him to act. When Tom tries to fatally beat the psychotic Noel to death, Frank defies him and saves Noel’s life (thus breaking the curse that’s been following Frank around for a while). This move towards risk again, at the potential cost of disappointment and failure, causes Frank to let go of his crippling fear of death, and the reality of not being able to save someone, and actually helps him lean into that uncertainty.

In accepting human frailty and finitude, especially his own, Frank is then able to do an even harder thing: he euthanizes the suffering and comatose, Mr. Burke. Frank sacrifices his own idea of who he is (as a savior of man) by using death to ease another man’s suffering. Paradoxically, this frees him to face his own ghost.

The Ghost

Unlike his three shift partner ghosts, Frank’s Ghost is a more literal apparition, the vision of a girl he tried and failed to save, Rosa. On a snowy day in his memory, Frank and Larry tried in vain to resuscitate an asthmatic and homeless 18 year old. As Frank fumbles to insert an air tube into her lungs (he keeps getting it into her stomach) she slowly dies right in front of him. Because Frank feels her loss (and every loss) so deeply, he continues to see her face on people around town.

“All bodies leave their mark,” he says, “You can not be the newly dead without feeling it.”

Over the three days, he sees her face in the face of prostitutes, in the face of gang-bangers, in the pregnant woman in the crack house, and on every stranger in every city street, Rosa is everywhere. To block out her haunting accusatory eyes, Frank goes to extremes to dull the impact and lessen the likelihood of her showing up again, from avoiding any calls from the dispatch that seems to point to the possibility of people in danger, to self-medicating into oblivion with too much coffee, too much alcohol, and too many drugs.

Frank has no filter or self-preservation by the time he and Tom are working together:

“It’s great to be drunk. Sobriety is killing me.”

“Our mission is coffee, Tom.”

“I’m driving out of myself!”

While under the influence of a mystery pill he is offered in a dank Hell’s Kitchen “opium parlor”, Frank has a hallucination of a street full of ghosts crawling up through the sewers. He reaches out a hand to each one, and pulls them back up to the land of the living.

If not for the grace of Mary, he might still be swimming in this sea of ghosts.

My ghosts (to just get the Cage stuff scroll down)

Click here for the personal stuff

My ghosts are my own, and I don’t think I can describe or paint a picture of them as artfully as Scorsese did with Frank in Bringing Out the Dead.

While I was in China, trying to “save the unbelievers” from their sins, members of my own family were dying back home. An aunt got cancer and succumbed, and then my grandmother. As these griefs weighed on me, I was still a few thousand miles removed, able to keep some emotional distance from their impact.

But then my other grandmother died and it broke me. We all succumb at some point to our own mortality. I didn’t grieve because of the reality of their mortality or my own; you start to expect that age will come and that annihilation will take us like seashells wiped away in a swiftly retreating tide. And as Frank describes it, “This city doesn’t discriminate. It gets everybody.”

In my grief, I was just experiencing what so many others have experienced in much more tragic circumstances. But I couldn’t shake the feeling of ghosts hiding around that unprocessed grief.

And, to add to the weight of this grief, I was also experiencing another kind of death: a loss of identity. As I began to realize I was not the bulletproof savior I had envisioned myself to be, I began to question the premise itself.

A savior? From what, and why?

Why was I there in a foreign country expounding a faith I no longer believed was true? Was there a God out there in the void attending all these ghosts? Was there a god in the silence that was even attending to me? The prospect of a god like that became doubtful and then insidious to me.

Like Frank, I was losing my faith completely. After three years in China, I returned home–defeated. But also free. And all I could see was the various specters of my own failure. I had sought to “save” others and I had sacrificed myself; my identity; my own sense of self worth. For what? Who was I now without my power to save?

My Ghost

And then I saw my Rosa. Reeling from the loss of both an identity and a faith, I learned that my “Rosa”, a dear friend, a woman who shared a “messiah” complex connection like I had, had died–worse, she’d likely taken her own life.

Her loss felt much more personal to me even than my family members dying. It was more tragic and unexpected and brutal. While we had not shared the closeness of life long friends, we shared a connection that’s hard to describe unless you’ve been in this type of “faith” culture.

Many years before, I had helped usher Rosa into the Christian faith. I had shared my truth with her and encouraged her to follow God as I had. We traveled with other weirdos like us to far out global locations to share our faith with unbelievers–whose language we did not speak, whose faith we did not understand. We prayed. We fasted. We shared Bible stories and our over-cocky 20-something wisdom with any poor sap who would listen.

I had taught, by my example, Rosa how to “listen to God’s voice” and obey it and how to love others like I imagined God would. She in turn helped me realize my vision of going to China and follow my missionary dreams. She sacrificed for me and spent her last dime to help me and my family pay for our trip to our promised land.

And years later, after Rosa and I had slowly lost touch with one another through the years, long after I left for China and returned to my homeland, she was already dead.

What I didn’t understand, which had been the case for many years, were the mental health issues Rosa had struggled with. Sadly, her story is much more tragic than suicide–if that’s even possible.

Rosa, my friend, years before taking her own life, had murdered both of her small children.

All of this happened while I was away in China. Reading her story in newspapers, I learned how she told police that she had “saved them” from the darkness inside of them. During the trial, her defense pleaded not-guilty by reason of insanity–since she reported herself to the police at the time and had no awareness of what she had really done. The boys were barely 2 and 5 years old. She suffocated one with a pillow. She drowned the other in a bathtub.

The ghost of Rosa, for me, was that her “messiah-fueled” schizophrenia birthed a God who made her his puppet–his Angel of death. Hadn’t I been a pupet too? But she’d taken the lives of two innocents believing she was the very hand of God–his mercy.

And the question I am wrecked with is “what if?”

What if Rosa hadn’t tried to hear God’s voice, or obey it, or even listen to it? Would her house slippers have whispered this same horrifying command–or did this blood hungry Judeo-Christian God-figure I introduced her to, fill a unique and evil void that the demon-chemicals of psychosis longed for? I don’t know the answer to that, but it haunts me still.

So, I see Rosa’s desperate and loving face smiling up from the past, up from the grave. I see it in the long gone image of my broken and fragmented faith. I see it in my own failures at being a savior and a human. Like Frank’s city, Rosa’s ghost “does not discriminate. It gets everybody.” Or at least it gets me. Every single time I think of it.

There’s something about Mary

The one character I haven’t said much about in the film is Mary. Mary Burke (Patricia Arquette) is the daughter of Mr. Burke and she’s Frank’s love interest in Bringing Out the Dead. But to call her a love interest is highly reductive in light of the role she plays in this story in her own right and specifically in Frank’s redemption (?) if that’s even the right word for it…

All saviors, wanna-be or otherwise, need a Mary I guess. Jesus had a couple Marys in his life. Mary his mother and Mary Magdalene, the ex-prostitute who purposefully poured a bottle of expensive perfume all over him much to the campaign fundraiser, Judas’, chagrin. (It’s a bad look and think of all the campaign financing we could have done with the proceeds.)

Mary and Frank meet while Frank is trying to pump her father’s heart back to life. They meet again at the ER where her father keeps flatlining only to be zapped back to life again. (Incidentally, they meet in the ER waiting room guarded by one of the baddest security guard cops from any movie EVER, Griss (Afemo Omilami).)

They meet once again at Mary’s house, Frank follows her there.

Frank orders her a pizza which she nibbles on in the waiting room (since it’s not really from her favorite place.) Frank and Mary meet again and again.

Mary opens up to Frank, telling him how she hates that her father is “tied” down with life support systems and medication. She hates that her old high school pal (and part-time psychotic) Noel is physically tied up in the hospital to prevent him from drinking too much water which will react negatively to his medication. She lets him go. I think Mary hates that both she and Frank are “tied” by invisible bonds to this neighborhood that they both grew up in with all its past ghosts. Mary wants everyone to just be freed; but in Hell’s Kitchen, it’s much easier said than done.

We know that Mary also had a drug problem in her past, and that when the stress of her father’s hospitalization gets to be too much, she returns to her old flophouse where she used to score a fix, this time “just for a little rest”. She asks Frank to come and get her after fifteen minutes, but by then she’s too far gone to just escort out of the place. Frank has his own little drug trip, flips out, and then physically carries her (fireman style) out of the druggie apartment.

Tempers boil, Frank falls asleep on her couch, and when he awakes she is gone.

But Frank fights his way out of hell on the last night. Despite (or because of) Tom’s violence, Frank is pushed to risk the “hard cases”. He saves Noel from the brutal beating that Tom gave him. Frank saves the drug boss that he met when Mary went for her little heroin nap, even risking his own life to do so.

And paradoxically, Frank takes Mr. Burke’s life in another act of courage, when he commandeers his life support system so that the man passes without alarm into a calm death. This saves Mary and her father from the purgatory of pain she is in since Frank realizes that Mr. Burke will never revive and never be the man he was before.

But it’s only when Frank goes to Mary to tell her of her father’s passing that we realize that she was the key–or a key to Frank’s forgiveness. After he has told her the somber news, that her father has died (sparing her the details of his own involvement) Frank sees Rosa’s face in Mary’s. He says “Forgive me, Rose.”

She replies in Mary’s voice, “It’s not your fault. No one asked you to suffer. It was your idea.”

One can hope that Frank has said goodbye to Rosa, that this is the last time he will see her face haunting him in the night. One can hope that Frank has received forgiveness from himself most of all–for being human, and limited, and compassionate.

The last scene shows Frank in a halo of light, resting on a bed with Mary. He lays his weary head against her chest as if he will finally find the oblivion of sleep he has longed for so many nights. While this Mary may be Frank’s lover, in this last scene of holy passion, Frank is the dying Christ in Michaelangelo’s Pieta, and Mary is his mother. Readying themselves for a resurrection.

My Mary (to just get the Cage stuff scroll down)

Click here for the personal stuff

If there is courage in me, like Frank, to not be some kind of savior–to live a life outside of the messiah-complex, it has come slowly as I have had to let go of that high, and that illusionary drug, and those lies I was telling myself about myself.

If there is an innate power in me that lets me love people and be a good human just because and not for some other god-motive or out of obedience to an iffy dogma, I have found that sense of purpose because of a similar solace to Frank’s–in the people I see and a person I know.

In my life after China, in my life after Rosa, in my life after Christianity, I find this same kind of love, forgiveness, and understanding in the eyes of my wife, who has always been there at my side. Like me she has limits, blind spots, and shortcomings, but that’s why we work so well together. We know these things about each other. And it’s OK. I have rested my head on her in so many ways. She has had to bear witness, bear grief, bear longing, and bear depression for me (and with me), and she has had the grace and mercy and love to stick with it and remind me that, “It’s not my fault.”

In some ways it was always my idea to take on way more suffering than I ever needed or want to.

And ya gotta let that shit go. I’m trying to. It’s hard, but I try. I am so grateful to her for having that Mary kind of love (and to Mr. Cage and Scorsese for reminding me again why I need it so badly.)

Frank sums, it up very well, the movement from savior to human, “After a while I grew to understand that my role was less about saving lies and about bearing witness. I was a grief mop. It was enough that I simply showed up.”

The rest of the formula

This has become quite a long post and more personal than what I had set out to write! Thanks for hanging with me through it to this point. If you think I’m just reading a lot of my own religious experience into this film, well, here’s a summary of the religious symbols or mentions in the film. You tell me if this seems like a coincidence.

- Noel begging for a cup of water multiple times – “For Christ sake, can I please get a cup of water.” Gospels mentions this example in a parable. When someone asks for something as simple as a cup of water, decent humans are obliged to give it and this is the measure of love, for it might be Jesus who is actually asking for that water. Accept him, you get it. Reject him, well, there’s another place for you to go…

- Frank resurrecting people out of the sewers.

- Idea of saving people mentioned by all of the ambulance drivers

- 3 Day shift (like the 3 days from Jesus crucifixion to resurrection)

- “Came out of the desert” – Noel (Noel is seen as a bit of a psycho and so was John the Baptist who lived out in the desert and ate crickets and raved like a madman.)

- Asian street preacher, “If you can find even one who isn’t a sinner…” This town is like a Sodom and Gomorrah and therefore subject to God’s wrath and destruction, but that doesn’t prevent Frank and the boys from trying to save people (who may not be worthy of it? is the question)

- Marcus bringing back I.B. Banging from the dead by gathering a prayer circle of his skeptical friends.

- “The first step is love, the second is mercy.” Marcus

- Holy Cross / Sacred Heart where the schools that Mary and

- Frank and Marcus, helping deliver a child in a crack house (to virgins) Maria = A “miracle”

- Marcus screaming about the holy ghost (after Frank quits)

- The drug boss gets impaled, looks like he’s on a cross hanging over the city

Best Nicolas Cage quotes (not already mentioned) as Frank Pierce

“Things had turned bad. I hadn’t saved anyone in months. I just needed a few slow nights, followed by a couple of days off.”

“It seemed all my patients were dying on me.”

“Shut up! You’re gonna die. He’s not gonna die.” Frank to Noel, clarifying that one was going to get to die liked he wish while the other is going to be saved.

“If you let go, I SWEAR I’m not gonna kill you.” Frank again using Noel’s carrot (dying) as manipulation.

“You swore to fire me if I came in late again.”

“My mother always said, I look like a priest.”

Firsts for Nicolas Cage as Frank Pierce

- Ambulance driver

- Euthanizing someone

- Giving mouth to mouth to a baby and mental patient

- Punching a desk two times in frustration

- Divorcee

- Resuscitating a whole bunch of people

- On a wild drug trip turned full freakout

- Surviving a flipped ambulance car crash

- First time starring alongside his wife (at the time)

Recurring

- Second movie with John Goodman (Raising Arizona)

- Third movie with Ving Rhames (Con Air, Kiss of Death)

- Smoking (Multiple)

- Shown wearing tighty-whitey briefs (Red Rock West, Moonstruck)

- Alcohol addiction (Leaving Las Vegas)

- Punches roof of car (Multiple)

- Ordering or eating pizza (Multiple)

I promise the next one will be shorter. Much shorter. It will be Gone in 60 Seconds.

Leave a comment