Nothing quite stirs up the literary artist’s sense of existential dread, self-loathing, and self-doubt like sitting down with your keyboard to the abyss of the blank page. Yet there is always the underlying if futile hope of creating something new and original. In all that intimidating white space, one is confronted with one’s true core. Pretense is stripped bare, all masks removed, hiding places revealed and left awash in the stark light of day.

The brilliant idea and the compelling story (or lack thereof) are all that the writer aspires to, and for some this process of creating real meaning from a bunch of words (of dredging epiphany from the sewers within) can feel almost excoriating to the soul.

Such is the case for Charlie Kaufman, the screenwriter at the center of a meta-film about a screenwriter writing the screenplay adaptation of a well-loved but structureless book about flowers (The Orchid Thief) based on real life events of a writer (Susan Orlean) and her outlaw botanist friend/lover/subject.

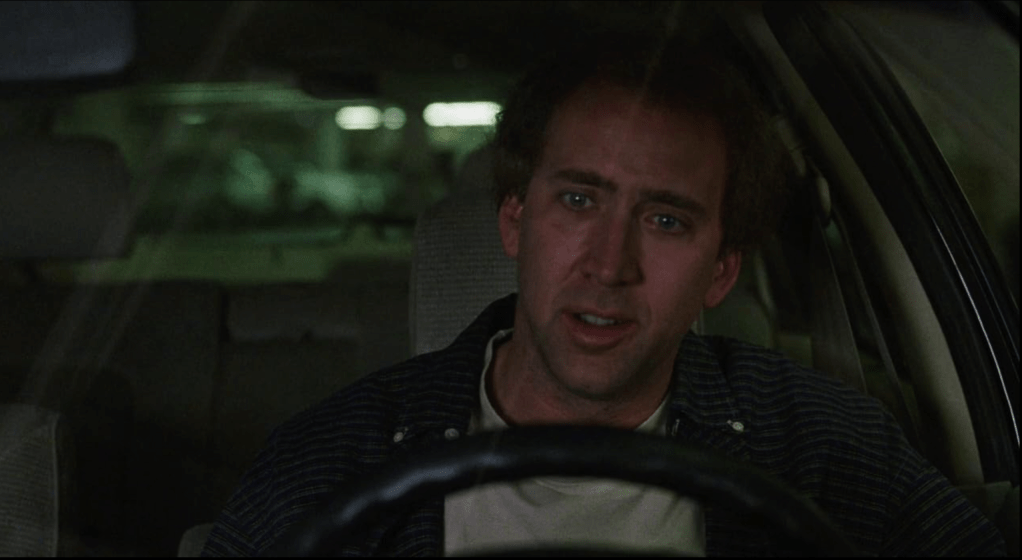

Portraying a neurotic artist like Kaufman in such an unconventional script, could only be handled by an equally talented acting savant. Someone with a reciprocal amount of neurosis, inspired genius, and unconventional approach. Someone, for example, a lot like Nicolas Cage.

Sound intriguing?

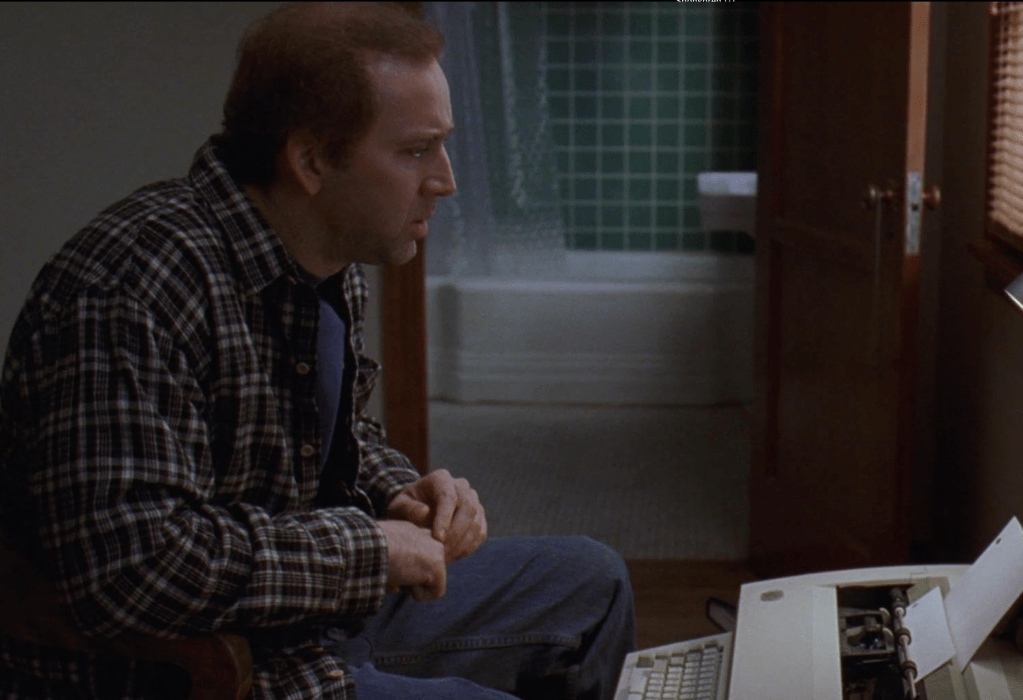

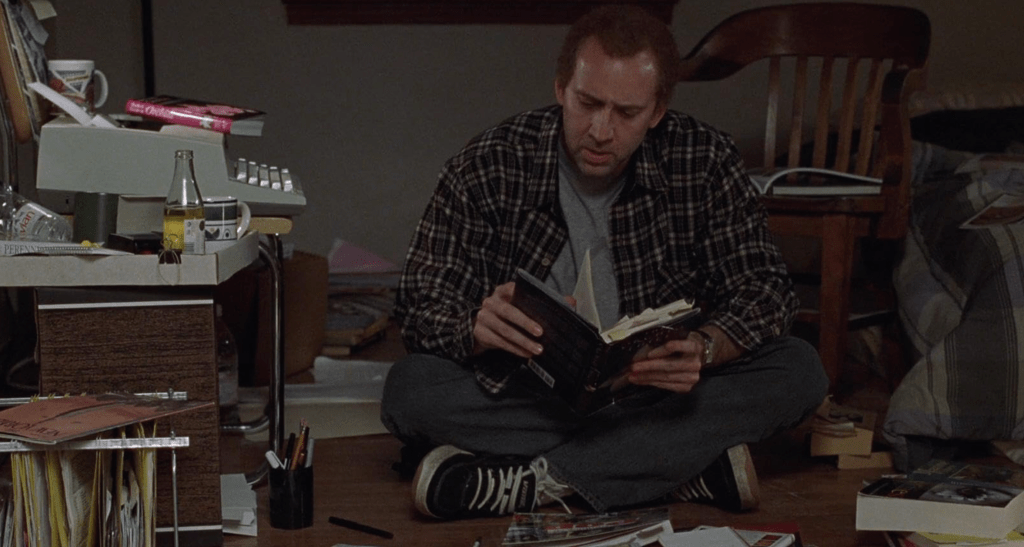

Well this is exactly what we were treated to in the bizarre and beautiful Spike Jonze film, Adaptation. (2002): Nicolas Cage playing two characters the fat, bald, and sweaty Charlie Kaufman and Charlie’s fictitious and gregarious twin brother, Donald Kaufman as they attempt to write screenplays while navigating Hollywood romances, bro stuff, and the paralytic power of writer’s block.

The film was highly acclaimed by critics, was nominated in multiple categories for Academy Awards, and likely influenced many films that came after through its inventiveness, meta-narrative structures, cinematography, and excellent cast performances. And even with all these things going for it, Nicolas Cage didn’t win the Oscar for it (losing to Denzel, for Training Day? Really?) Nicky stole the show once again (even from the very capable co-stars Meryl Streep and Chris Cooper). Seeing the range that Cage has in playing two characters like the Kaufman’s just adds to his acting mystique.

Which brings us to…

The World According to Charlie Kaufman (the writer)

Charlie Kaufman’s meteoric rise as a screenwriter came with the screenplay for Being John Malkovich, a story about a hidden room/portal in an office building that would allow the film’s characters to jump into the mind and take control of the real life John Malkovich. This highly clever and inventive film (if you’ve seen it) gives you some idea of the type of insular creativity that Kaufman brings to his craft.

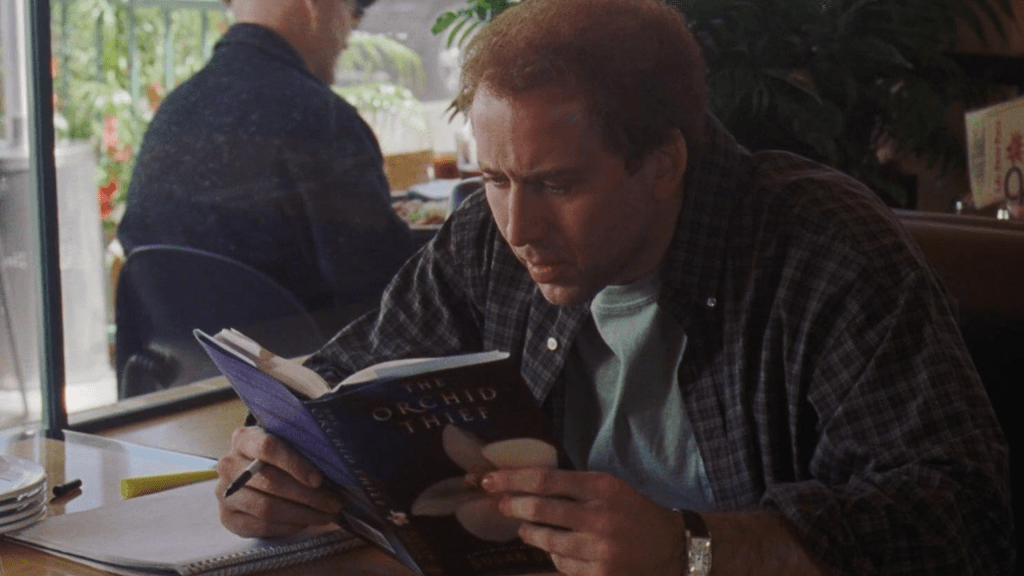

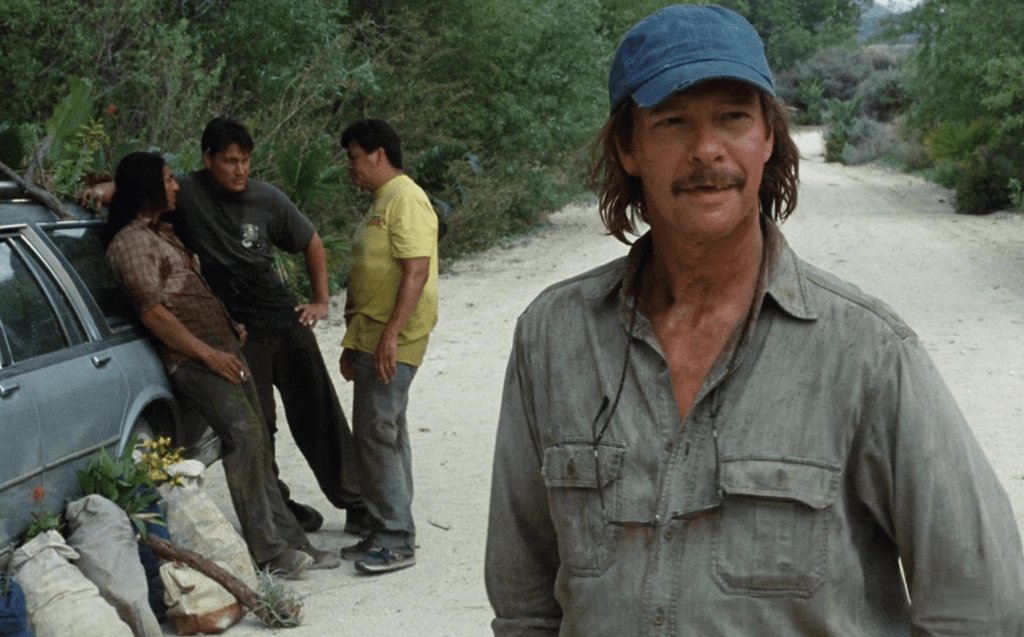

But in Adaptation., we are taken into the mind of the creator himself, Charlie Kaufman, a writer who is severely neurotic, full of self-doubt, and blocked creatively. In fact, the film was supposed to be a straight-forward “adaptation” of Susan Orlean’s book about an orchid thief, John Laroche, who was helping Seminole Indians in Florida steal orchids from federally protected state parks.

But real-life Charlie Kaufman was having trouble turning a structure-less sprawling story about flowers into a compelling film. (Evidently he wrote and turned in three different versions of the script, thinking his last version would never be produced. It was.) To solve his writer’s block, Charlie ended up committing the cardinal sin of screenwriting for a biographical adaptation–he wrote himself into the plot and narrative of the film. So the film is just as much (if not more) about Charlie Kaufman and the creative process than it is about orchids, desire, suffering and the other heady themes presented in The Orchid Thief. The content may center on the film version of Susan Orlean (played by Meryl Streep) and her intimate relationship with John Laroche (played by Chris Cooper) but it’s the psychology of Charlie and his fictitious twin brother Donald that builds the tension and drives the action. Through voice-over narration, we hear every secret thought of Charlie Kaufman as he struggles to write his script and live his life. We see every fantasy, every failure, and every envious or doubtful thought that passes through his brain.

As the young ones like to say, it gets “pretty cringe” at times, as looking into anyone’s mind (even our own) so deeply and unfiltered will reveal things we’d rather were left hidden or unvoiced. That kind of vulnerability can be a bit too personal to share.

The World According to Charlie Kaufman (the character)

“Do I have an original thought in my head? My bald head. Maybe if I was happier my hair wouldn’t be falling out. I’m a walking cliche. All I do is sit on my fat ass. If my ass wasn’t fat, I would be happier. Why should I feel like I should have to apologize for my existence.”

Nicolas Cage looks fat playing Charlie Kaufman. In fact, he wore a fat suit for the role. His wiry Richard Simmons hair is thinning noticeably all along the crown. He’s visibly sweating in half the scenes. The stream of consciousness above is just a sampling taken from the opening scene of the film in which he is running through a laundry list of all his life failures, his bad decisions, and the things he’s going to start doing tomorrow to improve himself. He’s obviously entering that quarter- or mid-life crisis period where he is questioning everything he’s become and flinching as he wonders when the next failure is going to strike.

It’s highly relatable to anyone who has insecurities (i.e. everyone) and shows artfully the way the inner critic is always there to eviscerate a creative person who is just trying to do their job (i.e. create something new).

I love it. And I hate it. In some ways it’s all too realistic, too vulnerable, too reflective of negative self-talk that plays on a loop inside my head at times, when I am struggling to find that mute button within. Regardless of the success he’s had or his intelligence and capability, Charlie faces that imposter syndrome that is ever fearful that someone will notice that he’s somehow less than he purports to be.

For Nicolas Cage, this is new territory. He has NOT played any character like this in his career. To be blunt, Charlie Kaufman is a dweeb. He’s his own worst enemy. He’s an overly-sensitive over-analyzer who is spiritually stunted by his own self-doubt, inertia, and timidity. And what’s worse, he’s highly aware of these shortcomings and often still can’t overcome them.

But at the same time that you are repulsed by all you see and hear from Charlie, you are also drawn into his struggle. He endears himself to you because you want him to overcome himself, to get the script written, to have more compassion for his brother, and live up to his own potential.

A long interlude for summarizing the movie (skip this if you’ve seen it or don’t care for it)

The movie begins with Charlie attempting to write the movie adaptation of The Orchid Thief while flashing back to his conversation with the movie producer (played by Tilda Swinton), watching the making of Being John Malkovich as he lurks onset, and having very-annoyed conversations with his good-natured twin, Donald, about how Donald is also taking up the screen-writing craft just like his brother–working on his “genre”, a thriller. Charlie is frustrated with his life, by the fact that he is so timid (and invisible to women), by the fact that he can’t seem to find the narrative arc of The Orchid Thief, by his literary desire to not make a Hollywood movie that takes sensational shortcuts with sex, drugs, and violence, and by the fact that the task before him is impossible: to make a movie about flowers compelling and interesting.

Charlie cannot handle the pressure of all of these things (and his looming deadline) and often flies into magical fantasies where he masturbates to Susan Orlean’s book cover, while she praises his literary prowess, or the waitress from his local diner suddenly strips topless to make love to him at the flower show. While Charlie dreams of these other lives he’s not living in the flesh, he struggles to write the screenplay. We are given flashbacks of what’s in the book through Susan researching the book through interviews and visits with John Laroche in Florida. It’s there that she learns about the tragedy of Laroche’s life story and his current obsession with these rare orchids.

Laroche, a highly self-educated “Florida man” / huckster / fly-by-night entrepreneur, has had one of the worst runs of bad luck in narrative history (I’d warrant) losing his wife (to coma), mother, and front teeth in a tragic car accident he caused, only to then lose his business (a nursery), and later the marriage, to the physical and economic devastation of Hurricane Andrew.

His scheme to steal flowers from protected Florida lands seems to be the latest in a long line of ill-advised plans, but one in which he is currently succeeding due to native rights and legal technicalities. In spite of all this, or perhaps because of the resolute will of Laroche, Orlean finds herself attracted to both the man’s passion for collecting and his indestructible and apologetic nature for being himself. The relationship of the two plays out alongside historical vignettes of Darwin, bees pollinating flowers, and “survival of the fittest” historical violence and tragedy as Charlie reads excerpts of Orlean’s book from his bedroom.

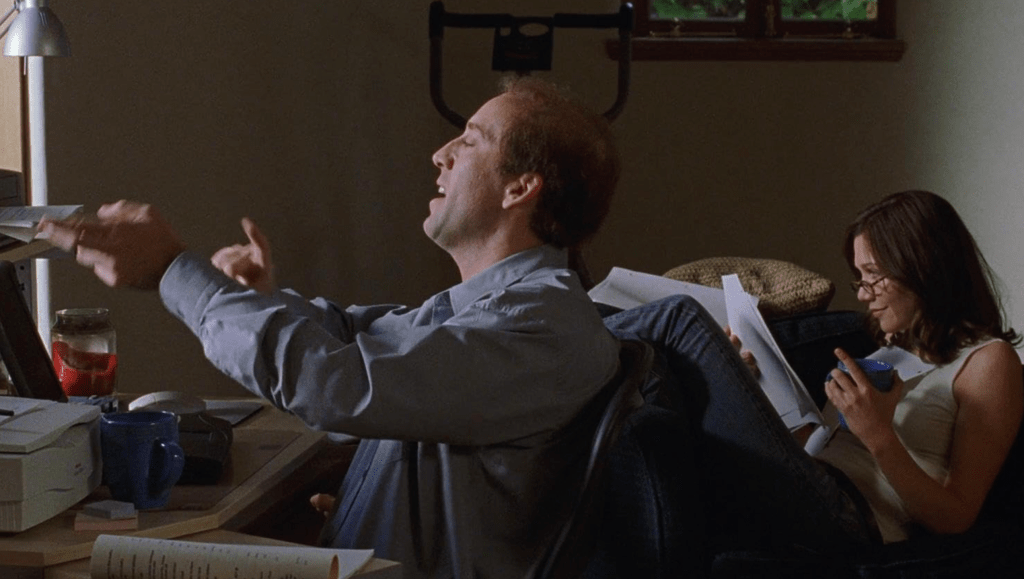

Interrupting Charlie’s neurotic fatalism and these story-propelling flashbacks of Laroche and Orlean, Donald tests Charlie’s patience on more than one occasion by cutting into Charlie’s his stream of consciousness narration, to give his (more experienced) brother advice on screenwriting which really gets under Charlie’s skin. Especially since the advice is coming via proxy from the lecturer and film seminar guru Bob McKee (played exceptionally by Succession’s Brian Cox). Charlie, who believes these types of seminars are really get-rich schemes and beneath a true artist’s sensibilities, and is dumbfounded by his twin brother’s new interest in writing and gullible belief that writing can be boiled down to a simple formula (e.g. McKey’s Ten Commandments). He can’t take his brother seriously, but Donald’s dumb luck and positive attitude won’t be denied, as he continues down the writing path, while easily attracting beautiful Hollywood starlets (although his frumpy appearance is identical to Charlie’s). Everything that Charlie desires seems to come effortlessly to his more affable (if simple) twin brother.

Charlie tries to negotiate his way out of his screenplay contract with his agent in New York, but fails. Charlie then plans to meet Susan Orlean in person to discover the “real story” behind her and Laroche’s relationship (which he starts to suspect might be more than just professional) but then chickens out along the way. Fearful that he can’t write the story, Charlie gets desperate and enlists the help of Donald’s protege Bob McKey by paying to attend one of his big seminars in the city.

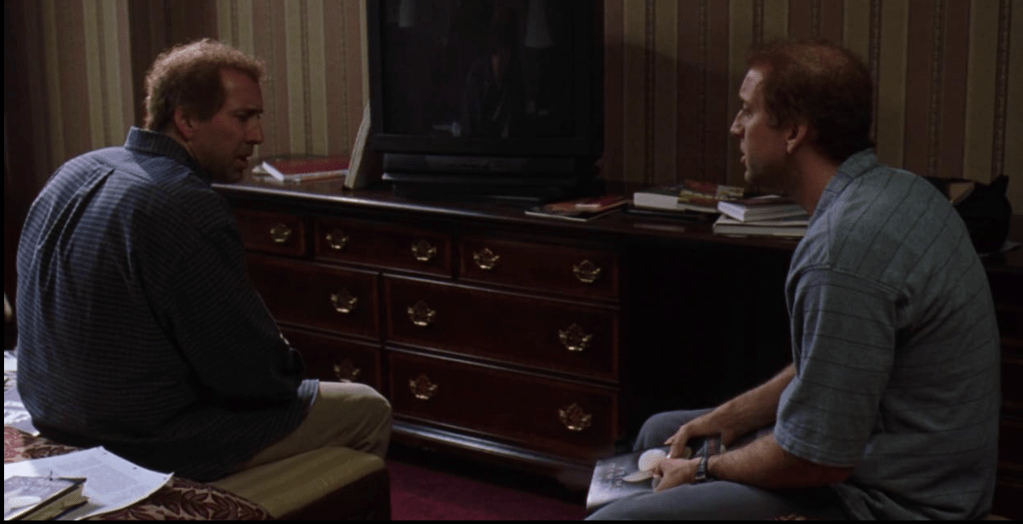

Fast forwarding a bit, Mckey agrees to meet with Charlie in a bar and tells him (after hearing a summary of the The Orchid Thief) that he can’t have a story with no growth or change in the characters, and definitely no story without drama. “That’s not a movie,” he tells him, “you gotta go back and put in the drama. Wow them in the end, you got a hit. Find an ending. But don’t cheat. And don’t you dare bring in a deus ex machina. Your characters must change and change must come from within.”

When Charlie tells him that he doesn’t know the angle or what the conflict is in this case: a story about flowers, McKey encourages him to “make it up”. McKey also points out that the greatest film of all time Casablanca was written by two brothers. This inspires Charlie to team up with Donald and get his ideas on how to finish his screenplay.

The movie takes a dark, exciting, sexual turn from there (according to Mckey’s advice) as the two brothers join forces and begin to “stake out” Susan Orlean in order to learn whether or not she is hiding something about her relationship with Laroche.

Of course (in this screenplayed bizarro version of reality) she IS hiding a love affair with Laroche, since the wild man has shown her not only the ghost orchid (in a Florida swamp), but also how the flower can be harvested and snorted for its hallucinogenic properties (just like the Seminole’s do in their rituals).

This drug experience frees Susan Orlean from her passionless existence and gives her a new sense of life, spontaneity, and personhood. But it is a hidden life from her husband and literary community back in New York. Donald’s detective work reveals all of these things to Charlie and the two brothers follow Suan down to Florida where the affair is taking place. When Laroche and Orlean discover they are being “stalked” by Charlie (and that he has followed them all the way to Florida) they decide the only resolution to keep their secret from the public eye is to kill Charlie. (This is Susan’s idea more than Laroche’s.)

But the two (presumed to be high) orchid lovers are unaware that Charlie has a twin and that Donald is waiting in the car for his brother to return. Planning to kill Charlie at gunpoint and dump his body in the swamp, Orlean and Laroche force him to drive his rental car deep into the Faxahatchee.

When they arrive, fearing his brother is going to be shot, Donald springs into action and saves Charlie and the two hide in the swamp all night.

Things get real-real real fast and Charlie gets shot in the arm, Laroche gets mauled by a gator, and while trying to escape from the two, Charlie crashes their car into a truck throwing Donald out the front windshield. Before help can arrive Donald dies as Charlie sings Happy Together to him in a muggy swamp. Charlie is left with an empty apartment, a screenplay to finish, and a girl friend to woo back to his side. As tragic as the ending is, it actually feels hopeful–you forget all the details that came before it and are happy with the outcome, however self-absorbed or outlandish they may have appeared on the surface. Kind of just like Bob McKey said. The two brothers produced a screenplay hit. And Charlie wrote himself right into the film. All the things that he didn’t want to do he did, and it worked out anyway.

The end.

What I loved about this film

Flowers are exquisite, beautiful, and passing. They run through the cycles and the circles of life. From seed to bud to flower–then they’re gone. Back into the earth to start over again. Sure, there’s the overt “survival of the fittest” story being told in Adaptation. and neither Charlie and Donald are “the fittest” and probably wouldn’t survive Darwin’s natural selection process, but with Charlie and this screenplay, there’s also the tragic side of the non-survival of the weakest. The raw exposure of human insecurity is on full display, in all of Charlie’s misgivings and self-doubt, the creative process that can be stunted, and paralyze us, the fear that we don’t have enough “passion” enough “beauty” or enough appreciation of that which is passing us by every day: our own lives. Our true desires.

Susan Orlean laments this lack of passion she feels, this void of not caring deeply enough. Of kind of being a spectator in her own play. She also is aware of the fleeting “vagabond” nature of Laroche’s hurricane passions. He easily discards them when they run dry as if “running away” from the commitment of loving something enough to stay through the ennui.

Obviously these are undertones, but I found them intriguing. I also love seeing Cage take on this type of role where an obvious genius (Kaufman) just can’t get out of his own way enough to do what needs to be done. He essentially has to create another version of himself (a narrative twin) in order to solve his problems, whether they be in his writing, in his love life (or lack thereof) or in the aggression needed for his own survival.

Such a stark contrast to what I remember of the violent and brash Cages in The Windtalkers or Snake Eyes.

The film also absolutely “nails” the struggle-is-real nature of trying to do justice to something with the written word. Taking one artform (a novel, a movie, a piece of music) and distilling it down to its textual essence. Using word to paint pictures that somehow still do honor and justice to the original. That shit’s really, really hard.

And I really, really appreciated Bob McKee’s writing advice delivered almost in the same apoplectic vein as Logan Roy might have delivered it. Here’s a few choice cuts from McKee’s lecture / seminar.

“You write a screenplay with out conflict or crises you’ll bore your audience to tears.”

“And God help you if you use voice-over in your work my friends. God help you. It’s flaccid sloppy writing. Any idiot could write voice-over narration to explain the thoughts of a character.”

Plus I was able to write down 8 of the 10 McKee Commandments that Donald taped over Charlie’s workspace before Charlie tore them down:

- Thou shalt respect thine audience.

- Thou shalt research.

- Thou shalt dramatize thine exposition.

- Thou shalt layer a subtext under every text.

- Thou shalt create complex character rather than merely, merely complicate story.

- Thou shalt use neither false mystery nor cheap suspense.

- Thou shalt not use deus ex machina to get to thine ending.

- Thou shalt not make life easy for thine characters (?)

Last note on what I liked

Cage is so funny, upbeat, likable and goofy (as Donald) and he is so cringey, tragic, embarrassing, and groan-worthy (as Charlie). You want to like him more than you do. You feel for the guy, but you also (maybe) see aspects of yourself (the worst and most insular) in the way he behaves. You find yourself going, “don’t, don’t don’t do that….c’mon.” Or, “no please, just kiss her or something.” And for the love of God, please “wipe that sweat off your forehead.” So much sweat.

What I could have seen less of

As much as I respect and admire her, for her craft, there were too many scenes with Meryl Streep in this movie. Tripping on “orchid” powder, making love to Laroche, at dinner parties, in the swamps of Florida. Maybe this is a nitpick, because it definitely was broken up over the course of the film, but still. Time spent watching those Orlean and Laroche was time I was not getting to watch Nicky do his twin thing. Which I kind of think needs to be its own sitcom: Charlie & Donny Talke in a Bedroom. I’d pay good money to see that.

This post has been a long time in the making and it already too long for sensible reading, so I’m going to cut to the lists now, but you really should watch this film at least once.

Firsts for Nicolas Cage (as Charlie / Donald Kaufman)

- First portrayal of painfully awkward, shy character

- Sweating profusely

- Talking to himself as a different character

- Hunched over a typewriter

- Failing to be a lady’s man.

- Masturbating to literary agents / book covers

- Speaking into a tape recorder

- Typewriting (while naked)

- Sleeping on his own (twinsies) shoulder in a Florida swamp

- Being shot in the arm (and surviving) while paradoxically simultaneously being in a car accident and dying (twinsies) note: this is some Schrodinger’s cat-in-the-box shit if ever I saw it.

Recurrences

- Second time appearing with Roger Willie (Windtalkers)

- Second time appearing with John Malkovich (Con Air)

- Second time appearing with Jon Cusack (Con Air)

- Second time appearing with Catherine Keener (8mm)

- In New York (Multiple)

- Singing (Multiple)

- Spying with binoculars (8mm)

- Looking at porn (as “research”) (8mm)

Best lines from Nicolas Cage as Charlie Kaufman

“I’m a walking cliche.”

“I’ve been on this planet for close to 40 years and I’m no closer to understanding a single thing.”

“A job is a plan. Is your plan a job?” Spoken sardonically to Donald [also what I am currently secretly voicing in my head every day to my 20 year old. Facepalm.]

“You and I share the same DNA. Is there anything more lonely than that?”

“Ourboros. I’m insane. I’m ourboros. I’ve written myself into my screen play. It’s self indulgent. It’s narcissistic. Its solipsistic. It’s pathetic. I’m pathetic. I’m fat and pathetic.”

Best lines from Nicolas Cage as Donald

“I meant to ask you. I need a cool way to kill people.”

“I’ll do it. I want to fix your movie, bro!” Donald

“You love what you love. Not what loves you. I decided that a long time ago.”

“A little push, a push, in the bush.”

“My genre’s thriller. What’s yours?”

Adapt or die, the cynic says. And there is some truth to that adage. The only thing constant is change, and Nicolas Cage never stops changing, adapting, and trying something new, and that’s why he’ll probably make another 100+ movies before I ever finish this marathon trek up the mountain of WATC(H). God bless his soul. He’s no Charlie Kaufman. He will adapt and survive!

Leave a comment