In Adaptation. (you’ll remember) Nicolas Cage plays Charlie Kaufman, a neurotic screenwriter who is experiencing the crises that every writer must face at some point in their creative journey: writer’s block. In it we get to hear directly from Kaufman’s angsty, slightly neurotic mind as he narrates stream-of-conscious thoughts on how he hopes to turn an unstructured novel into a compelling screenplay.

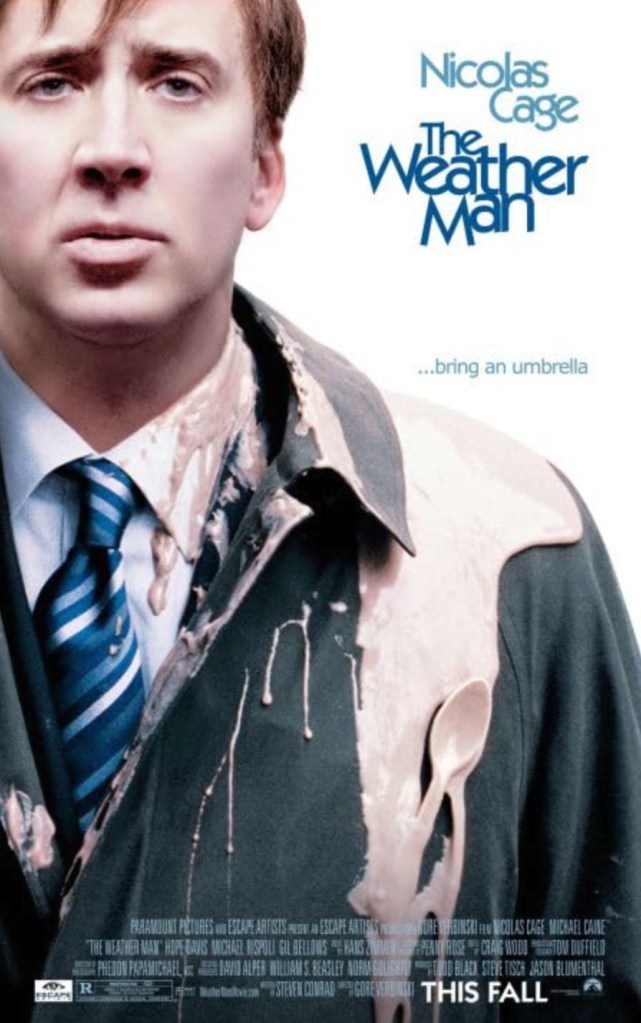

In The Weather Man (2005), Cage takes on another narration-heavy stream-of-consciousness character, in Dave Spritz, a Chicago weatherman, who is going through his own crises–a midlife crises. These films felt similar to me because they both allowed the audience to peek behind the curtain of the main character’s thoughts, and they both had a pretty high cringe factor in what they revealed about each man.

What Is This One About

Everything in The Weather Man centers around the weather, man, i.e. Dave Spritz, a career-driven TV personality who changed his name from Spritzl to Spritz because a TV exec felt it would appeal more to a viewing audience. I’m not sure if it’s technically a film about narcissism to the degree that Adaptation. most definitely is, but there were narcissistic tendencies and motifs throughout that drove the tragicomedy, and provided insight into this complicated “superficial” character who is living through his own midlife crises.

From the outset, the “weather patterns” of Dave’s emotional life are forecast through internal narration by Dave himself (Nicolas Cage) who seems as emotionally self-conscious and insecure about decisions as Charlie Kaufman, while holding a more elevated sense of confidence that his local celebrity status, career chops, and will power can somehow save him from the mess his life has become. From practicing his smile in the mirror each morning to tracking the incoming high and low pressure systems of turbulent family life, Dave tries to stay one step ahead of his separated wife who hates him, his two teenage kids facing social troubles and hidden adult dangers, and a highly successful and soft-spoken father who seems like a passively disappointed and confused by Dave’s life choices and failures.

Like I said, it’s really a movie about mid-life crises. The first time I watched it in my 30s, I really didn’t have enough life under my belt to fully understand its comedy or tragedy. The characters just seemed vindictive, self-centered and mean. Especially Dave. I didn’t share or understand Dave’s career ambition (at that time) nor did I see how that ambition that is meant to support a family can stand paradoxically get in the way of the family’s needs and values. My daughters were younger than the teenagers in The Weather Man, so I didn’t understand Dave’s inability to bond with his own children; how it’s possible to fail as a father because you don’t have a shared language or culture (or even proximal location) to lean upon.

All of these realities made a lot more sense to me as I approach 50 years. Though my life has been quite different from Dave’s, I could relate to the frustration, the alienation, and sadness of what he was going through.

And that’s all fine and good, mid-life is mid-life and should be highly relatable to me now, but what makes The Weather Man truly great is that it approaches this tired “genre” of mid-life crises in a fresh, often unexpected way.

There’s fast food, archery, and camel toe, Abe Lincoln milking a German barmaid, Bryant Gumbel talking shit, and Sponge Bob Square Pants floating down Central Avenue. What else can you ask of a Nicolas Cage film? The answer: nothing.

Does the Career Make the Man

One of the reasons I think this movie is about the intersection of narcissism and the mid-life crises is because Dave, the weather man, Spritz is convinced that his dedication to the meteorological pursuits is going to somehow turn back the clock on his marriage and miraculously fix all the brokenness of his familial fuck ups.

Dave has already lost his wife Noreen (Hope Davis) to another man (Russ). She likely dumped him for a long list of grievances (the last of which was an argument about forgetting to bring home the tartar sauce he promised to get, then lying about it to her). Dave has failed to notice his daughter, Shelly (Gemmenne de la Pena), for who she is, an overweight girl who spends book money on cigarettes and is mocked by her peers for having “camel toe”. He has also been absent from his son Mike’s (Nicholas Hoult) life, a youth recently returned from rehab for marijuana addiction, who seems to have landed in the grooming arms of a pedophile. With all of this in play, Dave has also failed to impress his Pulitzer-prize winning father Robert Spritzel (Michael Caine) who can neither relate to Dave’s career nor understand his struggles in the home. Robert played racquetball with President Carter on the regular, wrote best-selling works, and somehow still had time to love and nurture and support his wife and kids–why can’t David just “knuckle down” is the unspoken question in every interaction.

And even though his father, Robert is dying of lymphoma, Dave believes with the right career promotion to the nationally syndicated, Hello America, he can somehow impress his father at long last, re-adjust his children to health and wellness, and win back the woman that he loves. In some ways, it’s kind of the bizarro-world opposite-day plot to The Family Man (In which Nicolas Cage’s character is stripped of all his grandiose career aspirations in order to become the loving son-in-law, husband, and father he never got to be).

And the narcissism comes in in how Dave’s belief is completely detached from any semblance of reality. But that’s kind of how he operates throughout the film. In some ways, Dave is completely oblivious to how the world actually works. He appreciates his celebrity and that he gets paid an obscene amount of money for pointing at a green-screen (even though he has no formal training in meteorology) and yet he gets annoyed when people at the DMV approach him for an autograph.

He creates a catchphrase, the Spritz Nipper (i.e. the coldest day in the forecast), to appeal to his audience but actually gets angry when real people on the street ask him what the Nipper is going to be. His need for privacy is understandable, but his lack of awareness as to how others view him or wish to interact with him shows how under-developed his EQ actually is. This plays out in other ways throughout the film, and especially so in this weird belief that his new job / promotion will save him and those he cares about from their flaws.

The scene where David is trying to impress his father by “nonchalantly” leaving his Hello America interview letter (opportunity) on the passenger seat of his car, where he knows his father will likely see it, is especially cringey to watch. At that point in the story, Robert fails to understand what his son’s career is even good for and why it really matters, and is leaving a doctor’s appointment with a heavy diagnosis. The timing is poor; the attempt is transparent; the solution helps no one really accept David himself. Classic tale of narcissism gone awry.

The career doesn’t really make the man, but no one bothered to tell David this and he just keeps doubling down on this premise.

Couples Therapy

The thing I love about David though is that he tries. He really tries. Many men who reach the mid-life crises juncture are completely checked-out and self-absorbed. Dave’s narcissism is constrained because he wants his father’s approval so badly and (conceivably) believes that being a good husband and father is still his duty as a man. He’s just really, really bad at the execution. He seems unable to know what it takes to be a good husband and father. Now some of this undoubtedly is due to selfishness, he’s no saint; but a lot of what gets David into trouble is that he legitimately can’t get out of his own way. Here’s a few Noreen specific examples:

- He wants to be with his wife again (at least in theory) and so he aims for sympathy (“my father’s dying”) and playfulness. He tries to chuck a snowball at her while her back is turned thinking it will be funny / whimsical. But the plan goes awry, and it hits her right in face, cracking her glasses. Rather than apologize (normal behavior) he tries to make excuses, (“you turned into it”).

- At couples counseling, at a prompt from the moderator, he tries to be open about something he’s never shared about with his partner and blurts out his “porn problem” to the whole group, but the question was supposed to be rhetorical–something to be written but not spoken aloud. Oops.

- To make matters worse, each couple was to write down this secret on a piece of paper, fold and exchange it with their partner, and then hold that secret unread as sacred and NEVER reveal it, as a show of trust. Of course, David ducked into the bathroom and read Noreen’s secret right away, and then proceeded to get angry and confront her later for writing that she thought his sci-fi novel was stupid and a waste of time.

It only gets worse from there, but you get the idea. David, for all his strategic maneuvering, can’t seem to stick the landing and keeps misfiring right out the gate…he gets petty and makes matters worse. Speaking of misfiring…

Archery & The Weather

David’s marriage is a mess, but his parenting life is not much better. In mid-life, as fathers, we often come to the realization that we have no idea what we are doing. There’s no roadmap, no manual for this. As our sweet simple children are hormone-transformed into raving young adult lunatics, their bodies, appetites, and personalities start to evolve and morph. And often, fathers can’t keep up with this metamorphosis. David’s father Robert seems more in tune with what’s going on with his daughter Shelly than David does. Robert says, “Shelly is grossly overweight and unhappy. I’m concerned for her.” He also goes on to tell David how the other kids are picking on Shelly and calling her camel toe (don’t worry, we’ll get to that.)

David decides he’s going to teach Shelly about archery because she expresses an interest and he wants a way to bond with her. You can tell this is mid-life dad trying to find some long-shot (pun intended) way of connecting again. He buys a package of lessons, a bow, a quiver full of arrows, and takes Shelly to a range. Shelly attempts to fire off a few shots that travel a foot or two. She winces as the arrow string snaps against her forearm painfully. That was the first and last lesson to be had. He and Shelly do not return for more lessons.

Later in the film, David decides he’s going to learn archery himself to take some charge of his existence and knuckle down for his family. He gets better lessons, the right kind of bow and arrow, and practices learning the art of archery. After some time, he improves quite a bit. He learns how to hit the target and is closer to the bull’s eye.

“It’s hard, but that one good shot makes you think you might be catching on.”

Excited, he offers to take Shelly out again with his newfound hobby and skill. Training her in the way that he has been trained, he teaches her the terminology, and is brimming with excitement that now she’ll shoot the bow and see what he has learned to enjoy from the activity. Instead she shoots the bow a little further and is ready to quit once again.

Frustrated, David asks Shelly why she wanted to learn archery in the first place. She said so she could hunt animals. Shocked, David can’t believe her interest in archery was really motivation for hunting. Unwilling to take his daughter out to hunt and kill animals, David is at an impasse with her that can only be overcome by taking her out and buying her some new clothes.

But the archery motif is interesting to me because so much of David’s strategy and tactics seem like a man’s haphazard attempt at throwing things at the wall and seeing what actually sticks. Even with his career in meteorology, there’s a high degree of variance in his prognostications that he has trouble stomaching. Things might go one way, but they are just as likely to go another. This uncertainty (of mid-life) is scene symbolically in all the harsh weather patterns we are given throughout the films. Ice floes on lake Michigan, cold rain, sleet, flurries, pouring rain, snow accumulation, wind, and flurries. We get it all in the atmosphere and David gets it all in his emotional stratosphere.

The archery then is a salve for David because he can aim, release, and shoot along a specific line of sight. The one thing he is attempting to hit, he actually hits. Over and over and over. This is the opposite of the life he is experiencing with his family. Archery is achievable; it’s a predictable arc from point A to point B.

I think there is so much comfort in this for David that he starts to carry his bow and arrow around with him and by the end he is carrying it, draped over his suit and tie, as his “protective weapon” down the streets of New York. As he “let’s go” and releases his expectations on the type of husband and father he can be, he actually gains some precision and starts to hit his target more and more. Like he said, “he’s catching on.”

Dad Respect & Fast Food Chucking

As much as David is struggling in mid-life with his female relationships, he is also struggling in his identity as both son and father. Earlier I suggested that the career doesn’t “make the man” but that’s not entirely true. Men find their sense of worth in things like respect and honor, and much of this interplay is often mitigated through one’s career. Career is not the only factor that plays into male status in society, but it’s a pretty important one to the male psyche.

The daddy love stuff is pretty huge for David. Gaining the respect and admonition from his father is the Holy Grail that he seems to have been seeking (in vain) his whole life. David wants his father to acknowledge his career accomplishments, but to Robert his son’s entire career is an enigma as is the family struggles David is dealing with. Robert asks David to get him a paper, but David can’t make proper change so order himself a coffee.

“You should carry more than a dollar, David. You’re a grown man.”

Robert asks for his son to get him a coffee, but David has lent his wallet to his daughter and ends up only getting a soft drink for himself. These are all little failures that tell the story of many more failures where David has tried, but fallen short of expectations.

When David discovers that his father is dying, he internalizes the fact this way, “Don’t die on me, Robert. Give me time to get it together. Let me get the Hello America job. I can get it together.” This shows both Robert’s desperate need for his father’s approval, and his narcissistic tendency to make even his father’s death about him and his struggle.

But it’s the lack of bequeathed dignity from his father, that David senses (even though he can’t articulate it) that is the truly tragic / comic quality of their relationship. Throughout the film total strangers throw fast food at David on the street. In one scene his has been plunked by a Wendy’s chocolate Frosty. It oozes down his trenchcoat as his father, Robert approaches him. “What is that?” Robert asks.

“I got hit with a Frosty.” David replies, matter-of-fact. “People throw stuff at me sometimes, if they don’t like me.”

The dumbfounded look on Robert’s face when he hears this tells us everything we need to know about a father’s dignity and respect for his son. He is shocked at this treatment and seems to be victim-blaming David for this unmerited assault on his person.When addressing the struggles of his grandchildren or David’s marital strife, Robert often asks David, genuinely confused, “what is this?” but what he is really asking him is deeper and more cutting, “What are you?” or “Why are you…this way?”

But then it just becomes a vicious cycle because David again and again steps right into these unasked for situations.

He gets hit over and over and over again by fast food: Kenny’s roger fried chicken, tacos, falafels, Big Gulps, even a McDonald’s Hot apple pie. It happens so often, David tries to find the world’s reasoning behind it.

“Who gets hit with a fucking pie, anyway? Did anyone ever throw a pie at Thomas Jefferson or Buzz Aldrin. I doubt it, but this is like the 9th time I… clowns get hit with pies.” And this hits him like a revelation.

“I mean, I bet nobody ever threw a pie at like Harriet Tubman, the founder of the underground railroad. I’ll bet you a million fucking dollars…always fast food. Fast food. Shit people would rather throw out than finish. It’s easy. It tastes alright, but it doesn’t really provide you any nourishment. I’m fast food.”

Needing that high-brow kind of love from a high-brow kind of father is difficult for a fast food son. In fact, so difficult that David is unavailable to his own son when he needs him most. So much of David’s attention is used trying to appease his own father’s expectations, and his wife’s and their daughters, that he forgets all about Mike. Mike, who is sort of a side plot, is being groomed / wooed by an adult male counselor, who also happens to be a pedophile it seems. In exchange for gifts and favors, creepy Don (Gil Bellows) takes pictures of shirtless Mike and invites him out for movies and dinners. When he finally makes a move on the naive Mike, Mike reacts by throwing rocks at his car.

It’s only at the end of the film, as David is realizing that he can’t win his wife, life, and father’s love with a new job that he comes to his son’s rescue by beating the shit out of Don and thereby “fixing” his son’s legal troubles.

Father and son finally have a bonding moment together afterwards…where else…but at the local fast food court.

Camel Toe

It’s probably been almost, what 17 years since I saw this movie the first time, but I do remember the camel toe quite clearly. It’s the one thing I recalled about the film. If you don’t know what a camel toe is, try the Urban Dictionary. Or, just watch this movie. There’s a great scene that discusses what the term means, with helpful photographic examples of what it looks like, as well as the shocked look on a father’s face when he notices it’s presence on his daughter.

I had no idea about this phenomenon prior to watching this movie, so in one sense this is now an educational film. I have no idea if there is a more appropriate fashion or medical term for this, but this is what it will forever be referred to in my mind. Thanks, The Weather Man.

The funniest, and oddly most poignant part of this movie (other than the “good job son” scene we’ll get to) was the conversation between David and Shelly when he asks her what she thinks “camel toe” is and why people call her that. Her response, and his reaction, were sublime.

“Because camel toes are tough. They can walk all over the desert and all the hot rocks. I’m tough…I heard they make tires out of camel toes.”

Good Job, Son

Even within his narcissistic and mid-life stupor at times, David seems self aware enough to know when he is making the wrong move, even when he can’t help himself. When his son Mike is in trouble with the law, and Noreen’s boyfriend Russ is trying to step in and be a support for Noreen. While Russ is catching Dave up to speed on Mike’s current mood, Dave inexplicably slaps Russ across the face with his leather gloves.

He then reflects on this bizarre irrational reaction:

“Here’s something that, if you want your father to think you’re NOT a silly fuck, don’t slap a guy across the face with a glove because if you do that that’s what he will think unless you’re a nobleman or something in the 19th century. Which I’m not.”

But even with all the things going against him, David and Robert see eye to eye before he passes if only for a brief moment. It’s my favorite scene of the movie actually. Context is this: Robert’s pre-death celebration of life ceremony was cut short when the power went out, right as David was reading his eulogy. In it he mentions Bob Seger’s “Like a Rock” as how he thought of his father. But since he can’t finish the speech there’s no explanation.

Later as the father and son are sitting in David’s car, Robert is listening to the song, which he doesn’t fully understand still. You can watch the scene here.

In that moment of vulnerability, David shares how he beat the shit out of Don and fixed Mike’s problem with the law. Robert is happy to hear this and tells him so. Then David shares how he got the job at Hello America that he had been after. Genuinely impressed, Robert tells him, “That’s quite an American accomplishment.” It’s like a “good job” out of nowhere, that Dave has been waiting to hear his whole life, and the look of genuine surprise on Nicolas Cage’s face was acting gold. Then Robert asks, “Are you OK?”

And David breaks down and tells his father how, he “can’t knuckle down…” and essentially how he can’t fix his life with his wife and his kids.

In a show of real empathy and love, Robert tells his son honestly maybe the most revealing thing he has ever revealed, “This shit life. We must chuck some things. We must chuck them. In this shit life.” Then he grins (also acting gold) “There’s always looking after. You have time.”

Getting this atta boy from the man he has been trying to impress his whole life is the climax and the movie. It’s also especially well timed since Robert dies soon after. In some ways this ends the mid-life crises for David and launches him on a path to whatever is next for him. He does have to chuck some things, but he doesn’t chuck his bow and arrow, he doesn’t chuck his children, and he doesn’t chuck the thing he does best–predict the weather.

At an archery range in a wooded park, a fellow archer asks David a question about the upcoming weather, and he just tells him, without anxiety, fear, or doubt, “Who knows?” Which is pretty bad ass response based on what we’ve all seen so far from him. There’s a nice speech at the end on a float where he talks about his life not going as planned exactly, but at least he’s still in the parade line behind the marching band and ahead of Sponge Bob–and that’s something to hang your hat on I guess.

First for Nicolas Cage as David Spritz

- Career as a weather man (who doesn’t know meteorology)

- Time living in Chicago

- Looking pretty thin

- Going to Arby’s

- Dressed as Abe Lincoln (having sex with a German bar maid)

- Shooting a bow and arrow

- Air high fives no one (when his daughter didn’t reciprocate his attempt)

- Appearing in a parade with Sponge Bob Square Pants.

- Striking a man across the face with a pair of leather gloves

- Eating at the mall food court.

Recurrence

- Voice-over narration (Adaptation.)

- Waiting for people at a hospital (Bringing Out the Dead)

- Participating in a festive fair (The Boy in Blue)

- Trying to influence and impress his teenage daughter (Matchstick Men)

- Spending family time in department store (The Family Man)

- Hanging out in the dressing room with a young woman (National Treasure)

- Drinking hard alcohol in a solemn way in a hotel room (Leaving Las Vegas)

Quotable Lines

“Can you get out of my face? Can you GET OUT OF MY FACE.”

“I’m not a hill of beans. I have a plan.”

“You’re twelve years old. You shouldn’t be walking around without money. You’re not a kid.”

“You are a dildo. Pork fuck. Porker.”

“What if I’d remembered the tartar sauce. Would things be different?”

Leave a comment