Shortly before I started this WATC(H) journey, I randomly decided to watch Pig (2021) when it showed up on my Hulu recommendations. While viewing it, I remember thinking, Nicolas Cage is a pretty good actor, I should really watch more of his films.

Little did I know that I’d be watching (many, many) MORE (maybe too many) of his films over the next 18 months or so. And with this 100th film I was rewarded with one of his best offerings in Pig.

At the surface level, the film is about a downtrodden hermit who seeks to recover his stolen pet, a beloved truffle pig. Sounds pretty Disney, right?

But at a much deeper level, Pig is a deceptively complex story about refined society and artifice; the search for meaning and loss of faith; and the grief and alienation that exists within a family. And of course it is all of this–because those things make up the post-modern world–and who better than the our Misfit Messiah, Nicolas Cage, to lead us on such an underground pilgrimage of the fragmented Self.

The World According to Robin “Rob” Feld

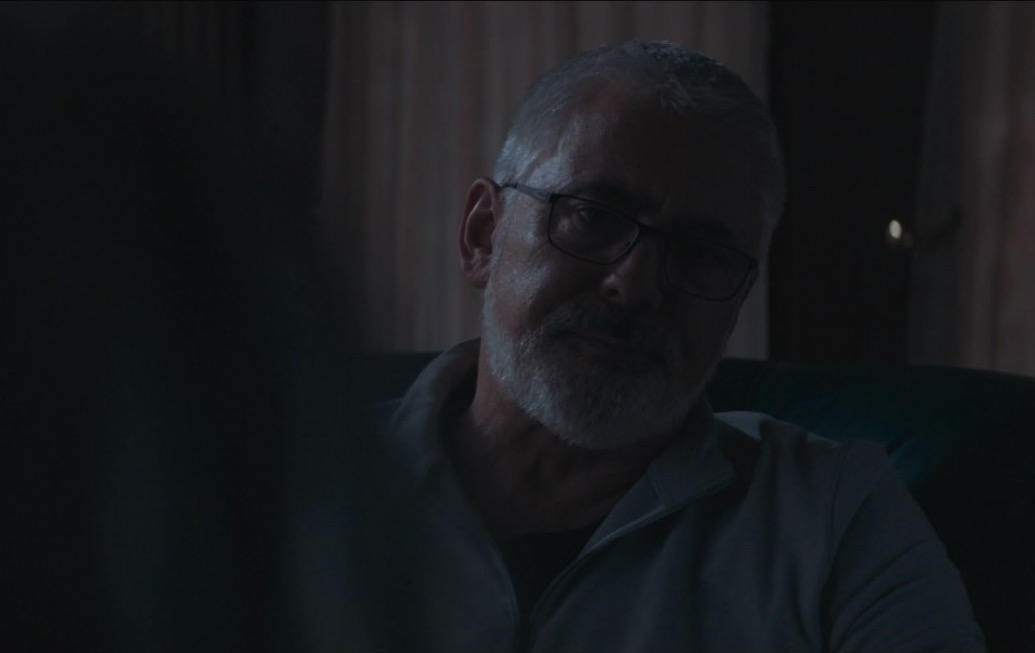

Rob (Nicolas Cage) is a hermit living in the Oregon woods in a small cabin with his truffle-finding pig. He sells / trades his truffles to a young organic food distributor, Amir (Alex Wolff) in exchange for other foods and items he needs to live on.

Rob seems as if he is living with PTSD of some kind as he barely keeps himself or his domicile clean. He has a long scraggly beard and gray / white hair, sleeps in filthy “Long Johns” that look like they may have been around in the early 1900s, has no electricity or indoor plumbing and seems to stay alive only through the food he cooks himself on his small kitchen stove.

One night Rob’s cabin is attacked by some tweakers who steal his pig and clunk him over the head with his own frying pan. Waking from this fresh trauma, bloodied but determined, Rob attempts to drive himself out of the woods to find and rescue his lost pig, but his car breaks down so he has to walk out of the woods to “civilization”.

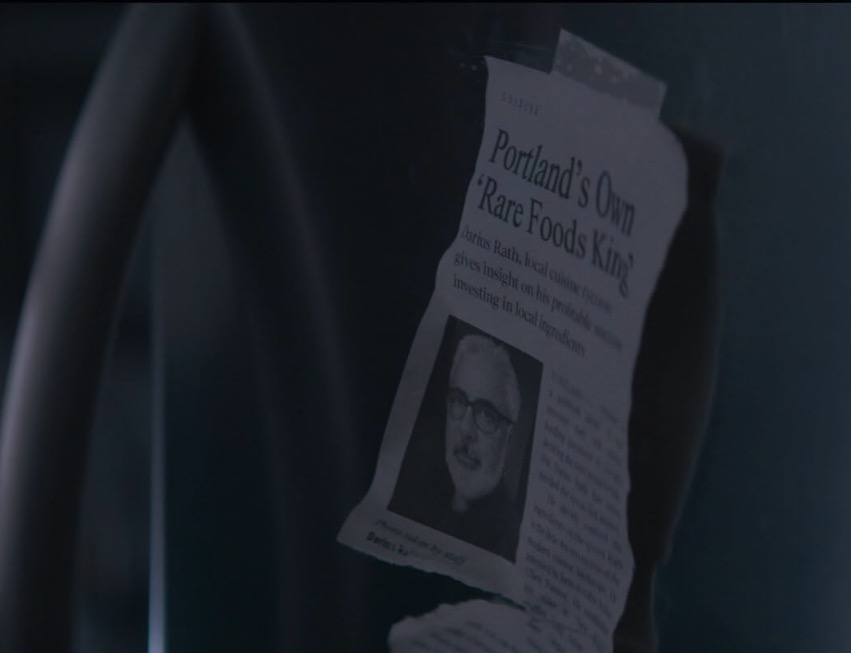

This is where the show gets really interesting because Rob finds himself traversing the “underground” organic food markets and Portland “foodie” scene in an attempt to locate the thieves who stole his favorite pet. Disheveled and disgruntled, Rob discovers that the tweakers were hired by someone from the city who wanted the pig for its truffle-sourcing super powers. Rob enlists the help of Amir who drives him into the city–where we discover that Rob, the unassuming hermit, actually has a complicated past. “Rob” was once Robin Feld, a renowned chef and a “power player” in the Portland culinary scene before “disappearing” many years before after his wife’s death.

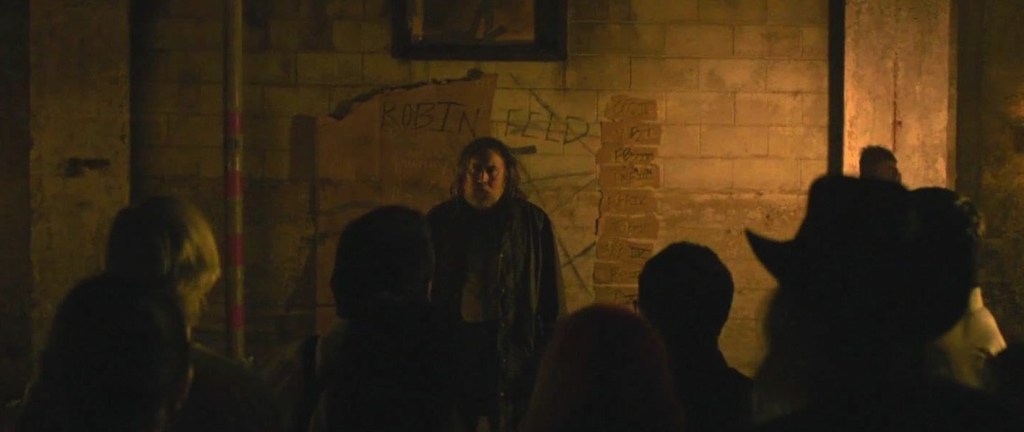

Through a series of networking connections and underground restaurant “fight clubs” a bloodied and bruised Rob discovers that the trail to his pig leads directly to Amir’s imperious and bullying father, Darius (Adam Arkin), who has made a career supplying food to upscale restaurants.

Darius has made it clear to Amir that he is not “cut out” for this business and has NOT offered any help to him. Through vulnerable discussions (and scenes) involving Amir, we also learn that Amir’s mother attempted suicide some time back and is being kept alive on life support in a facility by Darius.

Amir’s mother and Darius were seldom happy in their marriage, but did share one magical evening at Rob Feld’s restaurant (when he was the chef) and that night left a lasting impression on them and Amir (that he took from his childhood memories).

Rob confronts Darius about his stolen pig and Darius offers to pay any sum to Rob for the pig which he has evidently procured as a means to run his son, Amir, out of the business. Rob refused the offer since he has no desire to be rich, and just wants his pig back. It’s this petty, bullying behavior that makes Darius quite the nefarious villain, but the audience suspects that the tragedy that happened to his wife may be driving his ill treatment of his son.

Rob, determined to see the return of his pig, hatches a plot to connect Amir to his father and hopefully change Darius’ mind. With Amir’s help the two leverage food connections to gather ingredients from various restaurants. In Darius’ kitchen, Amir and Rob recreate the exact amazing meal Darius and his wife shared many years before at Rob’s restaurant. Cornering Darius, Rob and Amir get him to sit and eat the meal and drink from an exquisite bottle of wine (from Rob’s old cellar). The experience triggers Darius memories and causes him to flee the table with most of the meal uneaten.

Darius sequesters in his office where he makes himself a stiff drink. Rob follows him into the office while Darius yells at him to leave. Rob again tries to convince Darius to return his pig while Amir looks on from the doorway.

Pushed to the limit of his emotional range, Darius finally admits in tears that the pig is dead, that the tweakers had badly damaged it in transit and that it cannot be returned to Rob. Presumably, and this implied, Darius feels at least some regret (and anguish) over his part in this pig murder, and especially in the unresolved grief and what it has done to him and his son.

Rob is grieved beyond imagination and screams like an animal in pain as he falls to his knees.

HOWEVER, in an earlier scene, Rob has already revealed to Amir his secret–that he did not need the pig to find truffles –the trees tell him where they are located–and that having the pig had no bearing on his desire to have the pig returned to him. When Amir asks Rob, “Why then?” Rob tells him that he wanted the pig back because he “loved her”.

This type of love that drives a man to asceticism, to bodily harm and devolution, through this crucible of own grief (and the grief of others) is oddly parallel to what we see in Darius and Amir’s relationship, and their own stagnated ability to cope and love one another in a healthy way after the loss of their wife / mother. Keeping something “alive” well beyond it’s meaning or purpose–or keeping hope alive in the face of futility and opposition seems to be a central theme of Pig.

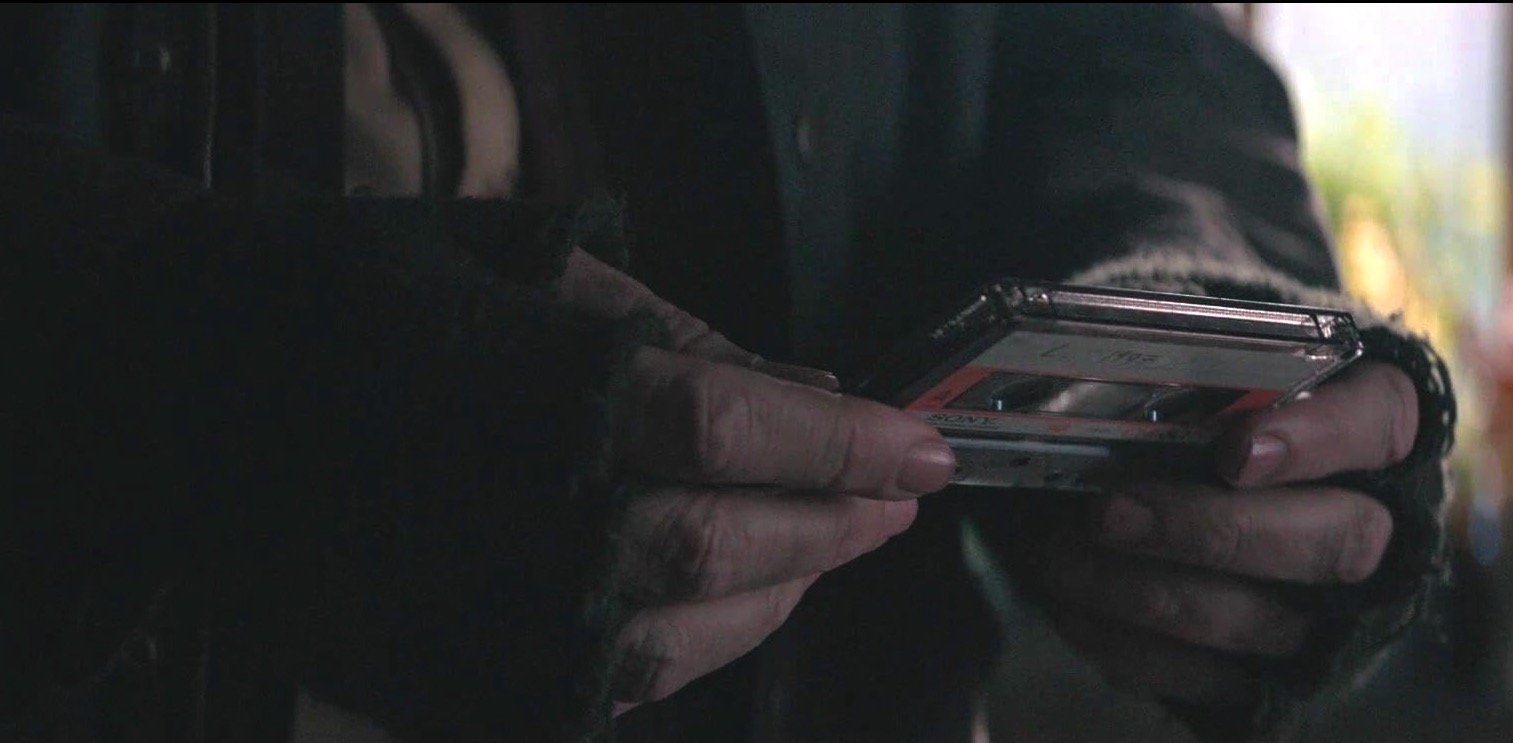

In the end, Rob returns to his cabin (getting a lift from Amir) and cleans the caked blood from his face (which has accumulated uncleaned over the duration of the film) in the river. He walks the forest, and upon his return to his lonely cabin Rob is finally able to take his shoes off and listen uninterrupted to the cassette tape of his wife, Lori, singing a birthday song to him–which he was not able to listen to earlier in the film.

The film ends with Lori’s joyous cover of Springsteen’s “I’m On Fire” playing as Rob stares up into the heavens of his small cabin.

The Power of the Three in One

Pig is a triptych.

A triptych (/ˈtrɪptɪk/ TRIP-tik) is a work of art (usually a panel painting) that is divided into three sections, or three carved panels that are hinged together and can be folded shut or displayed open. The triptych form appears in early Christian art, and was a popular standard format for altar paintings from the Middle Ages onwards. Christian triptych’s would often depict different scenes from the life of Christ.

Pig is a triptych in that the film is broken into three distinct parts / chapters, all of which are references to meals.

Part One – Rustic Mushroom Tart

Part Two – Mom’s French Toast and Deconstructed Salad

Part Three – A Bird a Bottle & a Salted Baguette

Part one is focused on Rob–he is introduced as a lonely figure who ends up losing his beloved pig and must set out on his journey (into his own past) to try and recover her. The Rustic Mushroom Tart is the first meal he makes in his simple cabin, from the mushrooms he has foraged in the woods.

In the first part, Rob is at the center of the action and he sets out on his journey “home”, finds his traveling companion, Amir, and then must face further hardships, getting “beaten” (quite literally) at Edgar’s place, in order to unlock the world that he has once been banished from.

(Granted this was kind of a self-banishment symbolically, not dissimilar to Adam / Eve getting dispelled from the garden by their actions. Rob chose to leave Portland and that life behind and now he is choosing to re-enter it–in order to find his lost treasure.)

Part two is focused on Rob and Amir–it’s about relationships. In Mom’s French Toast, we find Amir cooking for Rob. We learn about the broken relationship that exists between Amir and his Father Darius and how it centers on what happened to Amir’s mother. Rob’s search, which is now also Amir’s leads them to a fancy restaurant run by one of Robin’s former employees.

The Deconstructed Salad, represents the relationship that a cook has with his food (and / or the patron has with the chef). The food at this snooty restaurant type is the epitome of everything that Rob has left behind–food without soul, food that is not meant to fill or delight the senses, food that is so deconstructed that it no long can be called food.

In this interaction between Rob and his former Chef, Rob asks him about “meaning” (“What’s concept here?”) and if deconstruction is really why he became chef in the first place. This, too, is about artifice and meaning. Rob deconstructs the Chef’s entire existence by reminding him that what he really wanted to do was to start a pub.

Reducing the man to tears, he gets at the heart of the matter that he himself discovered about the service industry: this superficial culinary world cannot LOVE a person (or a chef) because it is impersonal, lacks relationship, and is not built to care. In defining this for the man, Rob again unlocks the next panel in the triptych: the person who stole his pig. Darius.

Part three is focused on the three men, Rob, Amir, and Darius. It is about reconciliation and grief and if we want to keep the weird Christian motif going–it’s a sort of warped take on a dysfunctional Trinity.

If Darius is the angry New Testament style father–who must take out his “holy” anger on the world (Amir / Rob) to appease his own wrath, and Amir is the dutiful son who follows and obeys his Father’s wishes (even when it’s obvious he probably shouldn’t) and is desperate for his approval, then Rob is like the Holy Spirit blowing through their world and bringing the flames of pentecost (a recognition) to their tongues (so to speak) that reveals to each of them who they are and the reality of the situation.

In this section we get to the truth of the matter. Through the Communion meal that is created by Amir and Rob, eating flesh (A Bird), the bread of life (Baguette), and partaking of the blood / wine (i.e. the Bottle) Darius is reminded of the life he had with his wife once upon a time–and in that memory he is enforced to embrace his own grief in what he has done to her (and is continuing to do) to his son, and the consequences of those actions that have played out in how he has impacted Robin’s life–i.e. accidentally killing his pig.

OK, I know that’s all kind of a stretch, but there is something here that points to a deeper mystery and I think The Threes peppered throughout are significant. There’s also an inverted nod to the parable of the Prodigal Son here, too. Intentional or not, I have no idea.

Follow with me: The Prodigal Son takes his father’s inheritance, breaks his heart, leaves his home / country, wastes the money on wine and women, and then ends up tending to pigs, envying them their scraps (which would have been a horrible fate for a Jewish man.) He then returns home pleading to his father for mercy / sustenance where he is reconciled and lavishly celebrated.

Rob, conversely, is living in a degree of squalor but relative happiness with his Pig, but must return to his home (a place that was painful to him) from his squalor, and reconstruct his life (symbolically) by taking back his status / name / relationships, and must reconcile two strangers (not family) Darius the father and Amir the son, showering on them with a forgotten blessing (a meal long lost) which reveals truth but does not ultimately bridge to forgiveness, lavish reward, or celebration. Rob instead is bereft of his lost treasure, and returns to his cabin alone.

Alive and Dead: The Buddhist Way

Another thing I noticed about this film at a philosophical level is this idea of something being “alive” and “dead” at the same time. There is a Buddhist undertone (or overtone) that all things are impermanent and that we should accept this if we are to have any hope with our human grief.

For example, Rob is most definitely still living after the loss of his wife, but he is so off the grid (and without relationships / community) it is as if he were dead to the world. In fact, when he resurfaces in Portland, those that once knew him almost voice this, “But I thought you were…” and Edgar (who did know him) actually says to him, “You don’t exist.”

Amir tells Robin that his mother “killer herself”, even though she is actually still “living” if on life support at a local facility. Amir wishes that his father had “let her die” as that was her intetion and being brain dead but on a breathing tube is the same as being “undead” most would argue.

At one point Robin returns to his former home in Portland and speaks with a young boy who now lives in his old house. They talk about a tree that used to be in the yard and the boy asks, “Did it die?”

Amir describes Rob as a Buddhist to one of the restaurant workers as a way to excuse his appearance, but it’s a subtle nod to both Rob’s asceticism and his outlook. At one point, Rob tells Amir essentially he shouldn’t feel bad about whatever is going on in his life because long ago the whole west coast was covered under the ice and water and some day it will be again (due to earthquakes, tidal waves, etc.) In other words, everything is impermanent and all we have is RIGHT NOW–without artifice and our illusions to distract.

So in reality, Rob is a Buddhist at his core, although he may not have wanted this life for himself. Grief made him go there.

Last Thoughts On The Good Stuff

One of the things I loved most about this film is that what is on the surface is not what is under the surface. What we think the “moral” of the story might be, is not what the moral ends up being. If there is a moral at all.

You think Rob is just a slovenly vagrant, but in fact he was once a world famous Chef and still can put together a pretty delicious meal–but he mostly chooses not to.

You think the world of culinary fine art food is refined and well-mannered. Well, in fact there’s a dark and hidden black market for ingredients; there are hidden fight clubs where restaurant workers pay for the opportunity to pummel chefs with renowned names and reputations, and the most pretentious and famous restaurants are also the most meaningless and least likely to serve food that real people would want to eat.

You think that Rob’s pig is the be-all-end-all answer to this equation and, of course, it will be returned to him in the end. How else will he find his truffles? But, no, nope. Life is full of unexpected twists and turns. The universe is not just, nor is it forgiving. Grief gets piled on top of grief, we see this reality for Rob. The pig is killed. The pig was not the key to finding the truffles, anyway. The story has no resolution–not really. Where is significance when all else is lost?

You think Rob will get revenge for his lost pig (or leverage to retrieve her) in much the same way Nicolas Cage characters do in every other vengeance film he’s in; i.e. through violence, theft, or lethal force. But no, Rob decides he’s going to “kill” Darius with kindness by springing an emotional trap on him. He serves him the most delicious and memorable meal of his life. He brings him back into the presence of his beloved. That’s some gangster shit right there. Unexpected.

And one more…

You think there will be (at least) your favorite dessert…Before Amir returns Rob to his shack in the woods, they stop off at a greasy spoon cafe. Amir wants some home made pie–some small consolation for all they’ve been through.

We don’t have any pie, says the waitress, which sort of shocks and disappoints Amir (and all of us, too). They settle instead for what is the available choice: a brownie or a cookie.

Sigh. Of course they do. Brownies, it is.

First for Nicolas Cage as Rob

- First time playing a famous chef (turned hermit)

- First time owning a truffle pig (or any pig for that matter)

- Sharing his dinner with a pig

- Living off the grid, in a cabin

- Participating in a Fight Club (get punched club)

- Wearing long underwear (as daily wear)

- Listening to a mix tape

- Hit in the head with a frying pan

- Allowing himself to be punched in the face repeatedly

- Kicking the shit out of a Camaro

Recurrences

- Living in the forest of the Pacific Northwest (Mandy)

- Trying to recover something precious that was stolen from him (Stolen, National Treasure 2, Pay the Ghost, Drive Angry, Honeymoon In Vegas)

- Steered to convalescence couch by a friend after getting beat up (Leaving Las Vegas)

- Taking off on a stolen bike (Prisoners of the Ghostland)

- Cooking a dinner for a family (Color Out of Space)

Quotables

“Good find, girl.””

“You want your supply, I need my pig.”

“Another pig can’t do what she did.”

“I might know someone; he knows the industry.”

“Have you heard anything about a pig?”

“I don’t fuck my pig.”

“I’m looking for my pig.”

“You should use stale bread for French toast.”

“Your dad sounds terrible.”

“None of it’s real.”

“We don’t get a lot of things to really care about.”

“I’d like my pig back.”

“Were you always like this, or was it just after she died?”

“I don’t need my pig to find truffles.”

[WTF did we do all this says Amir] “I love her.”

“Fuck Seattle.”

“Your son found this.”

“I remember every meal I ever cooked.”

“I remember every person I ever served.”

“If I never came looking for her, in my head, she’d still be alive.”

Conclusion

This little piggy went to the market.

This little piggy stayed home.

This little piggy had roast beef.

This little piggy had none.

This little piggy went wee wee wee, all the way home.

If you are a parent, you’re probably familiar with some version of this common nursery rhyme. It’s what I thought of as I was watching this film Pig for the third time. Rob’s pig went to the market, or to the city, but she never came home.

While sitting in the cafe during the scene near the end of the film, Rob, somewhat deflated, ponders aloud, “If I never came looking for her, in my head, she’d still be alive.”

Amir tells him sadly, “Yeah, but she still wouldn’t be.”

Rob agrees in a breathy way, “Yeah.”

Is Rob talking about the pig or is he talking about his wife? Was Amir thinking of Rob’s pig or had he internalized the question to be thinking about his “alive/undead” mom? Either or all three of these interpretations seem to apply and makes.

It’s a triptych sort of answer that hits on the many complex facets of a deeply felt and sadly uplifting film.

I can’t say for sure if Pig is my favorite Nicolas Cage film of all time, but it’s up there. Specifically, because of these meaningful philosophical questions it asks and leaves unanswered in such a gem of a creative movie.

This little piggy went…

Leave a comment